A coalition of research, government and industry partners is working to bring invasive sea urchins under control in Tasmania, with a mix of biological and market solutions

By Larissa Dubecki

It has been more than 40 years since the first Longspined Sea Urchin (Centrostephanus rodgersii) was positively identified in Tasmanian waters. In the following decades its numbers have exploded to an estimated 20 million animals along the island state’s eastern coast, progressively destroying large areas of shallow reef habitat.

The Shortspined Sea Urchin (Heliocidaris erythrogramma) occurs naturally in Tasmanian waters and exists in harmony with the local ecosystem. However, the Longspined Sea Urchin is an unwelcome visitor, and a badly behaved one at that.

It is also a native species but has reached pest proportions in Tasmanian waters after migrating south from its New South Wales coastal homelands. Thanks to global warming, which has strengthened the southward movement of the East Australian Current, the Longspined Sea Urchin can now be found all the way to Tasmania’s southern-most tip.

A program of research over the past 15 years, including work funded by the FRDC, has sought to quantify and understand the problem posed by the creature more colloquially known as ‘Centro’. Centro are voracious eaters of kelp and other marine plants. In large numbers, they can completely strip underwater reefs of vegetation, at first creating bare patches known as incipient barrens. If left unchecked, the urchins go on to create vast underwater deserts of bare rock, denuded of all plant life. These established barrens have a devastating effect on local marine life.

“I view Centrostephanus as a range-extended pest species,” says Ian Dutton, director of marine resources at Tasmania’s Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment (DPIPWE).

“They’re not just a Tasmanian problem; they’ve eaten their way through eastern Victoria’s marine systems as well. In Tasmania they pose a significant threat to our east coast habitats, fisheries and marine tourism industries.”

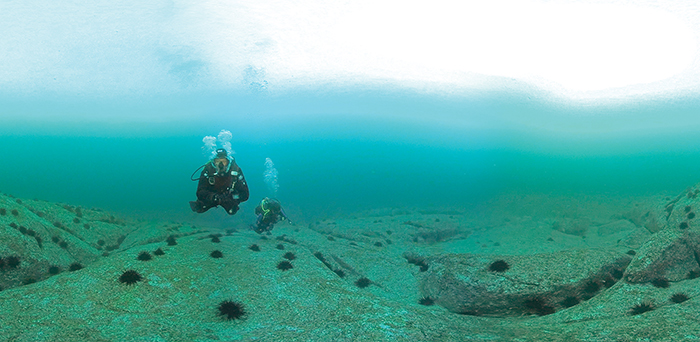

Tasmanian scientist John Keane measures sea urchins as part of research into control measures for this invasive species. Photo: University of Tasmania

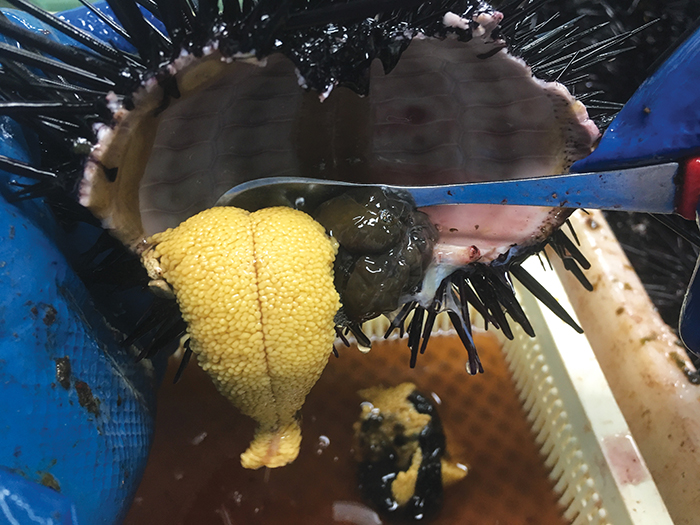

Known as uni, sea urchin roe is a delicacy in Japan. Photo: PauaCo

The first extensive FRDC-funded assessment of the Longspined Sea Urchin’s impact on Tasmanian waters was released in 2005. It warned that, in parts of southern NSW, urchins had removed entire kelp beds and created extensive barrens on about 50 per cent of the state’s shallow rocky reef habitat. It concluded that Abalone and rock lobster production would be lost from those patches of reef converted to barrens.

Subsequent studies have shown that in Centro’s Tasmanian epicentres, particularly around St Helens, barrens have grown alarmingly over a relatively short period of time. An FRDC coastline survey in 2001 found urchin barrens accounted for about three per cent of the state’s eastern reefs; 15 years later that figure had grown to 15 per cent. On a particularly badly affected part of the coast around St Helens, 37 per cent of the reef habitat had been overtaken by urchin barrens.

“The best way to describe it is a moonscape,” says John Keane from the Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies (IMAS) at the University of Tasmania. “In one-kilometre stretches near St Helens there’s just nothing to see except bare rock and the black dots of urchins.”

Control options

The larger members of Tasmania’s Southern Rock Lobster population represent one of Centro’s few predators. As it stands, however, Tasmania’s east coast lacks the biomass of rock lobster required to represent a viable biological control method.

“The rate of climate change on the east coast is benefiting urchins while disempowering predators like rock lobsters,” says Ian Dutton.

Working together, the Tasmanian Government and industry partners began a 10-year rock lobster stock rebuilding strategy after populations reached historically low levels. Launched in 2013, the program involved creating a separate management zone for the east coast, tracking catch within this zone, and capping the combined catch of both the recreational and commercial sectors to well below average historical levels. Since 2015, about 30,000 rock lobsters have been relocated from Tasmania’s south-west to incipient barren areas further north along the east coast. The strategy is on track to rebuild rock lobster stocks to greater than 20 per cent of the unfished stock by 2023.

However, even if the program proves a success, scientific consensus holds that in the short term, predators such as large lobsters are unlikely to be able reduce urchin numbers on extensive barrens to the point where seaweed can re-establish. Researchers have therefore turned their sights to other potential control methods.

Laboratory trials are beginning this year to test the feasibility of a technique known as ‘liming’ – piping calcium oxide (quicklime) to barrens. In Norway, where urchin and urchin barrens have been an issue for decades, this has proven extremely effective in killing the animals and aiding reef restoration.

The automated culling of urchins using robotic technology is another field of inquiry at the research and development stage, currently stymied by the considerable expense. The most direct and comprehensive methods of control currently employed involve direct removal or culling by commercial divers. Divers have culled Longspined Sea Urchins as part of research projects over the past

10 years, which has proven an effective approach to helping prevent specific patches of reef from turning into lifeless barrens.

An edible solution

In more accessible areas with higher catch rates, commercial harvesting has proven to be the most effective control option. While many Australians are unfamiliar with the taste and culinary uses of sea urchin roe, it is in demand in Asian markets – particularly Japan, where it is known as uni and commands a premium price.

The roe of the Shortspined Sea Urchin has traditionally been more prized for its sweeter flavour, but its inconsistent colour is a market drawback. The Longspined roe, while offering a stronger flavour, has been buoyed by its reliable golden colour, and it comes into season when the Shortspined Urchin is spawning and unsuitable for harvest.

The past few years have seen efforts to develop a quality product paying dividends both economically and environmentally. At the forefront of these efforts is RTS PauaCo, a stalwart of Tasmania’s Abalone industry on the south-east coast, which first ventured into urchin territory three years ago as an experimental response to a reduced Abalone quota.

“Without removing the urchins, the Abalone quota will continue to decrease,” says RTS PauaCo Group chief executive and managing director Beth Mathison. “We’ve spent several million dollars over the past three years refining the processes and reaching a point where urchin processing has become a viable part of the business.”

The latest FRDC report on the Centro problem, co-authored by John Keane and released last year, found the commercial harvest of Longspined Sea Urchins reduces Centro’s impact on Abalone and rock lobster fisheries, even with low levels of harvesting.

Centro catches over the past three years have seen more than 1000 tonnes taken from east coast waters. It has definitely had a positive impact, says John Keane; to what extent will be known later this year when another project re-surveys a previous habitat study done between 2014 and 2016.

“The removal is relative to recruitment,” he says. “Visually, it appears the divers are winning the war in some areas, and we want to quantify that. When you’re diving you can see areas where the kelp is coming back – all these lovely, juvenile kelp where once there were just urchins.”

A diver swims over an urchin barren, Tasmania. Photo: University of Tasmania

A helping hand

The adoption of a subsidy for urchin divers has been crucial to the crusade against Centro – and to the investment and growth of RTS PauaCo and a small number of competing businesses. The subsidy was initiated in 2018, with $5.1 million available over five years to support and increase the sustainability and productivity of the $90 million Tasmanian Abalone industry. It is administered by the Abalone Industry Reinvestment Fund, a joint initiative between DPIPWE and the Tasmanian Abalone Council.

“There has been a broad acceptance over the past decade that eradication is not possible and that we need to focus on mitigation,” says Dean Lisson, chief executive of the Tasmanian Abalone Council.

“The best approach from a sustainability perspective was to try and create a lasting industry based on the harvest of Centro, and to that end the creation of the subsidy has been the single most important thing to happen in this area.”

The subsidy to urchin divers has altered slightly as the program evolved. Initially, a single rate was provided along the east coast. However, now the rate increases for urchin harvesting towards the south of the state.

Most of the active urchin divers also hold Abalone diving licences. With recent quota reductions in the Abalone sector, the dual-licence divers have welcomed the additional demand for Centro by processors, which is underpinned in part by the urchin subsidy.

It offers both a crucial financial lifeline to divers and acts as startup funding, enticing fish processors into harvesting the urchins for their roe.

“It’s effectively removed over two million urchins,” says Dean Lisson.

“In the absence of a subsidy it would be a small fraction of that. The divers are looking at the ocean floor from the perspective of both species and they’re reporting a diminishing urchin population and an increase in seaweed, with the Abalone coming back.”

In Tasmania, invasive Longspined Sea Urchin is being harvested for its roe. Photo: PauaCo

Sea urchin steps ahead

The invasion of the Longspined Sea Urchin (Centrostephanus rodgersii) into Tasmanian waters has galvanised a coalition of government, researchers and private enterprise into an emergency action.

The success of this campaign to date will be followed by public awareness activities, highlighting the sea urchin problem and current progress.

Temporarily put on hold by COVID-19, an exhibition at IMAS’s headquarters on Hobart’s Salamanca Wharf will explore the journey of the Longspined Sea Urchin and the past 15 years’ worth of research. It will showcase what has become a positive environmental and industry story.

“It’s about the light at the end of the tunnel,” says John Keane.

“It’s unlikely we will ever eradicate it, but increasingly we have confidence we can keep it under control with minimal impact on other species, while gaining a healthy, profitable industry. It’s the culmination of 15 years’ worth of FRDC and IMAS projects, coming together into a story with solutions.”

Another positive step in the Centro harvesting story is imminent, thanks to the financial aid of the Abalone Industry Reinvestment Fund. RTS PauaCo has procured a Chinese-made machine that converts the urchin waste into valuable byproducts. After being delayed due to coronavirus, the machine has now arrived and will soon begin operating.

The roe accounts for only eight to nine per cent of the animal and the rest has traditionally been thrown away. Waste disposal adds a significant cost to urchin processing. The new technology, however, will enable the extraction of the sea urchin’s oil and the processing of the rest of the shell into products like organic fertiliser or fish and animal feed.

“It’s a great story,” says Beth Mathison. “You’ve got an invasive pest, you utilise all of the animal to establish an innovative and viable business and create jobs, you help restore the Abalone and crayfish habitat by harvesting the invasive pest species rather than wasting a resource.

It’s such a fantastic win-win for the industry and for Tasmania.”

In addition to roe, sea urchin byproducts will soon include oil and ingredients for fertliser and animal feeds.

Photo: PauaCo.

FRDC Research Code: 2013-026, 2017-049

More information

John Keane, Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies