Ocean modelling technologies continue to push the envelope when it comes to finding fish with greater accuracy in ever less-predictable circumstances

By Chris Clark

Australia’s Southern Bluefin Tuna (Thunnus maccoyii) fishery boats routinely travel hundreds of kilometres across the Great Australian Bight to capture live fish, which are then farmed in pens until they are market-ready.

The distances involved mean that fruitless forays are simply not an option for the Southern Bluefin Tuna (SBT) sector, which has long used forecasting tools to more effectively find their fish. But in season 2020-21, fishers used a new climate model, called the Australian Community Climate Earth-System Simulator – Seasonal (ACCESS–S) for the first time.

ACCESS–S is an upgrade of the Bureau of Meteorology’s legacy climate model Predictive Ocean Atmosphere Model for Australia (POAMA).

Southern Bluefin Tuna have become more widely distributed and harder to find as they travel along Australia’s southern coast.

Photo: Australian Southern Bluefin Tuna Industry Association

This latest forecasting technology has been developed jointly by the Bureau of Meteorology (BoM), CSIRO and the Australian Southern Bluefin Tuna Industry Association (ASBTIA) – the industry body for SBT fishers and farmers. The ACCESS–S project was born when the BoM decided to upgrade POAMA.

The project, co-funded by the FRDC and ASBTIA, uses a new state-of-the-art seasonal climate forecasting model developed by the BoM. This links it to an updated habitat model developed by CSIRO that is based on new fish tag data that tracks SBT behaviour. The result is higher resolution of mapping that identifies where SBT of different ages are most likely to be found.

The SBT fishery has become an increasingly challenging commercial prospect over the past decade or so because of changes in fish behaviour that are not well understood.

“Where we used to fish along 200 kilometres of the shelf break, it was easy to send boats and towing pontoons out and wait for the fish to school at the surface,” ASBTIA’s Kirsten Rough explains.

“Now, in some years, the fish are distributed across a thousand kilometres, so we need reliable and predictable areas that are consistently attractive to the fish for periods of weeks to months. That’s why this forecasting model has become essential.”

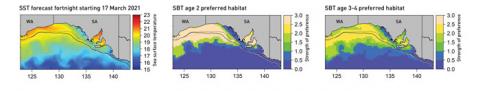

Figure 1: Forecast sea surface temperatures (SST) and corresponding areas of preferred habitat for Southern Bluefin Tuna (SBT) in the Great Australian Bight

Maps showing forecast temperatures and corresponding areas of preferred habitat for fish aged two and three to four, respectively.

Values > 1 indicate more preferred habitat, values < 1 indicate less preferred habitat. Source: Paige Eveson

High resolution

ACCESS–S increases the spatial resolution of the old ocean model from about 200 x 100 kilometres to 25 x 25 kilometres. “There is a lot more detail in the model and you can see oceanic features like eddies, if they’re big enough,” according to the BoM’s Claire Spillman.

ACCESS–S provides sea surface temperature (SST) estimates for up to six months for Australian waters see bom.gov.au

The estimates are run through the habitat distribution model to give a probability map of where tuna might be found. The forecasts are available at cmar.csiro

Industry-led research

The SBT aquaculture sector targets three to four-year-old fish for growing out, and was interested in having age-specific habitat models, says research team leader Paige Eveson, from CSIRO Oceans and Atmosphere. “They wanted to know if the conditions the younger fish were found in were different from the conditions for the older fish.”

And it turns out that quite small temperature changes can have a big impact on where different age classes of fish might be.

“The difference in preferred temperature is only about half a degree between two-year-old and three to four-year-old fish, but that’s enough to change the areas you would expect to find fish,” says Eveson.

This is critical because the feed costs of growing the fish to meet customer size demands can have a big impact on profits.

“Young tuna grow very quickly, and can double their size through the ranching period, but you still need the majority of your fish to be in a certain size range,” says Rough.

Fishers can see forecasts for up to two months to help plan their seasonal operations. These include the need to order in supplementary feed well ahead of the quota season opening on 1 December. Typically, by November they will be using spotter aircraft to find SBT schooling at the surface as water temperatures rise.

The fish can only be captured when they school at the surface, so being where the fish are is vital. It requires timely and accurate decisions on where to send the boats with the pontoons that will hold the live fish that are ultimately towed back to Port Lincoln in South Australia and grown to marketable size. It takes weeks to get the boats set up on location and many more weeks to tow a catch back to port.

Streamlined operations

Rough says ASBTIA needed intuitive and easy-to-understand forecasts. “One of the things that was very important with this project was to make sure information was easy to use and accessible.” This includes free access and an easy-to-navigate interface. “Limited phone and internet coverage at sea means you can’t waste time searching through website menus for information,” she says.

The updated model also includes habitat ‘nowcasts’, which provide estimates of where fish are likely to be found now, by combining SST and the level of chlorophyll in the water. Younger fish tend to be found where temperature and chlorophyll are higher. The nowcasts complement the habitat forecasts, which are based only on SST; ACCESS–S does not provide chlorophyll forecasts.

Rough says the nowcasts help fine-tune decision-making out on the water. “You can compare what you’re seeing on a daily basis from spotter aircraft with up-to-date temperature and chlorophyll data and then relate that to longer term forecasts for tuna size, based on age classes,” she says.

An updated version of ACCESS–S will be online later in 2021 and will include more of the BoM’s own data, which should further improve forecasting accuracy.

At CSIRO, Eveson says a fresh round of tuna tagging is also a priority because the current data is getting close to its use-by date. “The tagging data we’re using starts in 1998 and is quite extensive up to about 2010, but there hasn’t been a lot since. We need new data on fish behaviour because things have been changing, not only with the climate but also with activities such as oil and gas exploration,” she says.

Claire Spillman from the BoM says it has been satisfying working on a project with such a direct industry impact. “I think this is a really good example of applied ocean forecasting, and we’re one of the first groups in the world to do it. There are not many other industries doing this kind of work in the marine sector and there is a lot of opportunity and potential for growth there.”