An initial investigation into the presence of microplastics in seafood has found much smaller quantities in the guts of Australian marine species compared to those in many other countries

Words by Annabel Boyer, Illustrations by Nina Wootton

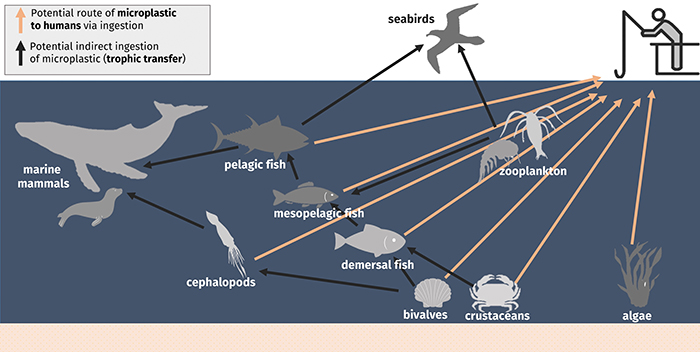

Plastic in the oceans and the impact it is having on marine wildlife and ecosystems has been sounding alarms around the world for some time. However, the potential impact that microplastics consumed via food may have on human health is poorly understood.

Although international research has tackled the issue, a recent FRDC-funded study is the first to investigate the potential impact on human health in an Australian context. In doing so, the study has provided Australia’s seafood sector and Australian consumers with the first verified data on the issue.

Principal investigator on the project, Bronwyn Gillanders from the University of Adelaide, says as the first study of its kind in Australia, the project is significant.

“It is the first lot of information that focuses on seafood sampling and highlights information around microplastics in seafood in Australia,” she says.

Identifying the issues

Gillanders says, “There has been a lot in the media around microplastics but, at the end of the day, if you don’t have that information, it’s really hard to make informed, evidence-based decisions.”

Previous work in Australia has confirmed the presence of microplastics in sea floor sediments, so this recent project set out to establish whether or not those microplastics were being consumed by marine organisms.

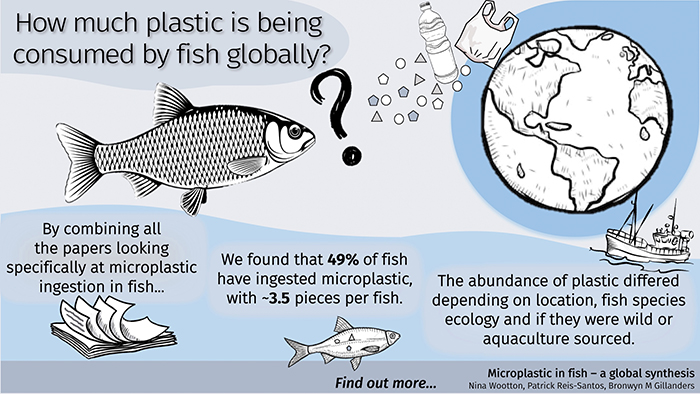

The study examined the frequency with which microplastics occur among finfish, crustaceans and molluscs collected from Australia’s commercial seafood markets, as well as the amount or load of microplastics present in each organism. It also conducted a literature review of similar studies around the world to compare where Australia sits in relation to other countries.

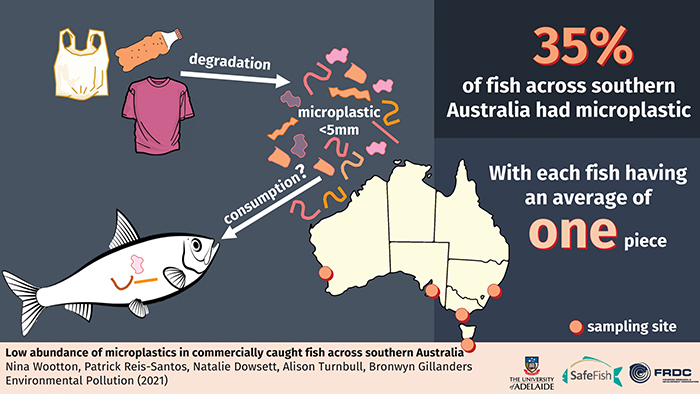

“We found that fish in Australia do consume microplastics, but it is at relatively low levels,” says Gillanders, “and slightly less than what you find everywhere else in the world, which is a positive.”

The project found that 44 per cent of about 1800 examined marine organisms contained microplastics, with no clear trends for the frequency of occurrence either by species or geographic region. The microplastic load (the number of pieces of microplastic) found in each organism varied widely.

In terms of the occurrence of microplastics found in seafood, when compared with other studies around the world, the occurrence in Australian seafood roughly equalled the median. However, with an average of 1.02 pieces per organism, the quantity of microplastics found in Australian finfish, shellfish, prawns, crabs and squid was low compared to many international studies.

Alison Turnbull from SafeFish, the FRDC-funded body that provides information on the safety of seafood for consumption, says the research goes a long way to allaying concerns about the issue for Australian consumers.

“At the moment, there is no indication that this is a human-health risk, but it is an area for future research,” she says. “The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization has advised that microplastics from food are not a risk to human health. At the moment, you would be consuming much higher levels of microplastics through your drinking water than through any seafood you may consume.”

“It’s also important to note that in this project we were looking for microplastics in the fish guts, where we anticipated them to be most prevalent, and mostly people don’t eat fish guts. Where microplastics are more commonly consumed is where you eat the whole animal.

“We did find some microplastics in oysters. But even if you ate bucket loads of oysters, you still wouldn’t be consuming as much as what you do through your drinking water.

“The questions that follow on from this pertain to all food and drink, they are not specific to seafood,” Turnbull says.

Australian methods

Gillanders says that, prior to about 2010, there were very few studies that looked at microplastics in fish and seafood. But growing awareness and concern has seen a boom in the number of studies.

“There are large numbers of studies focused on North America and Europe and fewer in the Australasian region, but their methodology and quality are varied.

“We looked at what we thought was best practice and what methods were used in other studies and came up with an approach that worked for us,” she says.

As an initial study, the FRDC project examined the digestive systems of 25 species of finfish, six species of crustacea, three bivalves and a single squid species for the presence of microplastics. The examination of the digestive system places the focus on whether these marine organisms do consume microplastics.

“All of the samples are species that are widely consumed. We got the vast majority of our samples through markets and they were all commercially caught. The species we used were determined by what we could get hold of for a reasonable price,” Gillanders explains.

Where appropriate, the gastrointestinal tract was removed from sample organisms. It was then digested or dissolved and the resultant material was sorted under a dissecting microscope. Plastic particles were counted for each organism.

Gillanders says this process is a departure from some previous studies, which have identified plastics using only the naked eye.

Nina Wootton, Patrick Reis-Santos, Natalie Dowsett, Alison Turnbull, Brownwyn Gillanders Environmental Pollution (2021)

Plastic validation

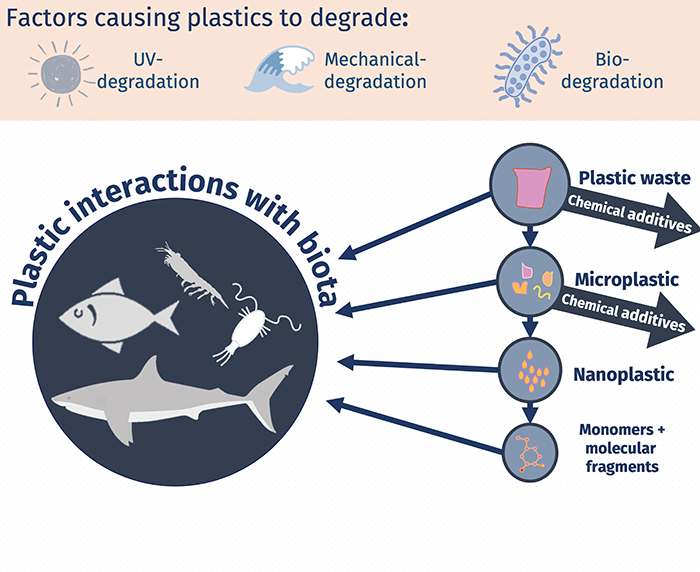

These results have also been verified with Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR), a method used to identify chemical compounds. Gillanders says this component of the project was vital, but has only been a recent development in this area of research.

Through further analysis of global studies, Gillanders’s team identified the need for consistent guidelines in methods used to evaluate microplastics in seafood. This could help to ensure data collected around the world is unambiguous, comparable and can be widely used to inform decision-making to manage and prevent any issues related to human consumption of microplastics through seafood.

Establishing the source of microplastics found in seafood can provide compelling information for decision-makers to manage the issue, such as when the Australian Government banned the use of plastic microbeads in cosmetics.

Gillanders says, “We used FTIR to confirm the presence of microplastics and then to further investigate what type of microplastic it might be. Is it likely to be coming from clothing or is it likely to be coming from plastic bags or something else?

“If you look at the Australian samples, a lot more of them had plastics from fibres whereas other work we’ve done in Fiji had film-like microplastics, from things like plastic bags.

|

Microplastics are small particles and fibres of plastic. There is no recognised standard for the maximum particle size but they are generally considered to be particles measuring less than five millimetres in diameter. This includes nano-sized plastics that are fragments measuring less than 100 nanometres. Source: FAO |

Future investigations

However, Gillanders points out that it is still unclear where and how fish may be consuming microplastics. “These are plastics that the fish have consumed, but whether or not the fish have consumed them within the environment or as part of the fishing process, we can’t be sure.

“We are now looking at whether microplastics are more likely to be retained in certain habitat types, such as seagrass and mangroves, rather than the adjacent soft sediment,” she says.

Although the project has provided some valuable information about the presence of microplastics within Australian seafood, both Turnbull and Gillanders highlight the need for further investigation about microplastics and human health.

Chief among these potential future investigations is to establish whether microplastics make their way from the gut of marine animals into tissues that are consumed. In Gillanders’s project, tissue samples from the research were frozen, which will allow them to be analysed for the presence of chemicals associated with microplastics sometime in the future. Work is underway to establish a satisfactory method to do this.

Turnbull says there are questions about whether microplastics are able to cross through the human gut, if they are consumed, and whether that may be cause for concern. There are also questions around whether microplastics are a source of harmful chemicals that may leach into the flesh of seafood used for human consumption.

“The future questions should include looking at nanoplastics, looking at what chemical contaminants are adsorbing onto plastic surfaces, and how they might desorb in the gut and across gut membranes,” Turnbull says. “If you think of it from a human health perspective, is this going to survive through our digestive tract?”

One of Gillanders’s students is already investigating how microplastics may change in the environment, to see what chemicals may be taken up by them and how that may change through time.

For Turnbull, an expert in the safe consumption of seafood, the more urgent issue continues to be the broader issue of plastic pollution, its impact on marine organisms and the environments in which they live.

“A bigger concern by far for me is the impact of microplastics and other plastics on the animal itself. That has a much bigger ecological impact and the potential to disrupt food chains than it has for human health risk,” Turnbull says.

Although Australian seafood consumers can enjoy their local catch without worrying about their health, the urgency to reduce plastic usage and prevent plastics from entering marine environments remains. f

|

“A bigger concern by far for me is the impact of microplastics and other plastics on the animal itself. That has a much bigger ecological impact and the potential to disrupt food chains than it has for human health risk.” Alison Turnbull, SafeFish |

More information

www.frdc.com.au/marine-plastics-impacts-and-policy-responses

www.safefish.com.au/Reports/Food-Safety-Fact-Sheets/Microplastics-in-Seafood

www.safefish.com.au/reports/food-safety-fact-sheets/microplastics-research-australia-new-zealand

www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/CA3540EN

www.gillanderslab.org/plastics

FRDC RESEARCH CODE

2017-199