As aquaculture progresses from niche to large-scale operations requiring teams of skilled workers, a major new venture, Project Sea Dragon, is creating economic development and job opportunities

Black Tiger Prawns (Penaeus monodon)

Black Tiger Prawns (Penaeus monodon)Photo: Seafarms Group

One of the largest agriculture infrastructure projects in Australian history, a massive aquaculture development across two states, has reached ‘shovel-ready stage’.

All planning, regulatory and Indigenous land-sharing approvals are in place for the first three farms (1120 hectares of ponds), allowing construction to begin as soon as finance is secured.

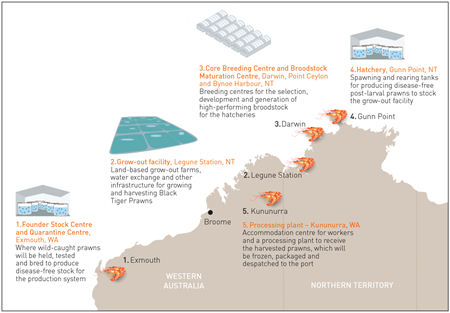

The venture, titled Project Sea Dragon, opened its headquarters in Darwin on 8 May and has been methodically assembled over the past seven years by the Perth-based Seafarms Group. It will be a vertically integrated marine prawn breeding, farming and processing enterprise linking five specialist facilities in Western Australia and the Northern Territory.

When fully completed in 2025, the project expects to achieve an annual production of 150,000 tonnes of Black Tiger Prawns (Penaeus monodon), valued at $1.7 billion in annual export earnings. It would take Australia from the 67th largest prawn producer in the world to among the top ten. Media reports have put the cost of the project at about $2 billion, and a number of large global seafood investors are reported to be in negotiations with Seafarms, with marine product giant Nissui recently signing on.

The project brings together ‘big science’ and ‘big commerce’ to ensure the operation starts on a large enough scale to be economic from day one. This includes 1120 hectares of grow-out ponds (each pond covering 10 hectares) on a cattle station, Legune Station, on the coast across the Northern Territory border from Kununurra, WA. The operation will have access to clean seawater, plus fresh water from a private dam. Its remoteness is also a crucial biosecurity measure.

Seafarms managing director and former manager of CSIRO climate research programs Chris Mitchell explains that the project is based on what he describes, and emphasises, as “fundamentals analysis”.

“The first fundamental was to look at demand and markets, to understand global population growth and, within this, a rising middle class that is increasing the demand for protein. The other fundamental is that the global wild catch has stabilised. These factors give us the macro problems – and the opportunities.”

In terms of aquaculture more broadly, Chris Mitchell sees it as part of the long continuum in food production, which has moved from hunting and wild catch to farming as the way to progressively lift food availability, yield, productivity and quality.

Source: Seafarms

Large-scale start

Chris Mitchell says Seafarms closely studied global aquaculture to gauge what is working and what is not. In assessing prospective sites for a large-scale venture, northern Australia quickly stood out – but with some well-known caveats.

“Northern Australia is highly prospective, and its isolation and clean water gives it a high biosecurity status, but every enterprise proposed or attempted in this region is confronted with the realities of scale. Unless you are able to conceive and implement something on a large enough scale, it is unlikely to succeed commercially. A small-scale operation simply cannot fund the infrastructure needed to operate profitably in the north,” he says.

Chris Mitchell says this also applies to markets and marketing – the need to demonstrate an enterprise has the capacity to reliably meet and grow demand, and to use scale to drive down production costs. He cites the Atlantic Salmon sector as a successful model. “So while we believe we have found the best grow-out site in the world at Legune Station, if we had sought to just put in 20 hectares on which to practise or prove the concept, it would not work, because it would lack the scale needed to prove the market.”

Having ‘pulled apart’ the aquaculture model here and overseas, Seafarms undertook a concept study: a pre-feasibility study incorporating an options analysis, principally considering different locations for operations; then a full feasibility study; and finally a combined ‘bankability’, engineering and design study. All of these stages involved extensive research and intensive negotiations with the WA, Northern Territory and Australian governments, particularly with respect to land tenure. Legune Station is a pastoral lease over which there is also native title, necessitating the negotiation of an Indigenous Land Use Agreement (ILUA) with the native title holders.

Disease-free stock

Overview of Project Sea Dragon facilities

Overview of Project Sea Dragon facilitiesSource: Seafarms

While all this was happening, Seafarms acquired Crystal Bay Prawns at Cardwell and Ingham in North Queensland to gain operational experience.

“The initial idea was to use the Queensland operations as a pilot study for Sea Dragon, but it was a conundrum because at Cardwell, for example, the technology is old compared to what is planned for Sea Dragon. But it has still provided invaluable knowledge.”

One thing the Cardwell and Ingham operations did reinforce was the need to start the Sea Dragon project with pathogen-free founder stock. Chris Mitchell says everything stands on this, and this work is already underway at a quarantine facility at Exmouth, WA. There, wild stock is being tested and bred to provide disease-free founder stock for the production stages to come.

Once the whole enterprise is up and running, it will start with breeding disease-free founder stock at Exmouth, which will be flown to a core breeding and broodstock maturation centre at Bynoe Harbour near Darwin. It will then go to a hatchery at Gunn Point, 80 kilometres north-east of Darwin, back to the 1100 hectare grow-out facility at Legune Station, and then to a processing and packaging plant at Kununurra.

The geographic separation of the facilities is partly because of the different infrastructure requirements of the various stages, but also because biosecurity is fundamental to the whole production cycle.

The facilities are separated geographically so that if a pathogen did breach the biosecurity defences in one location, the operation as a whole could be kept secure.

In terms of what comes next, Chris Mitchell says Seafarms is keen for people to understand that the project has already started. The Exmouth facility is into its second breeding generation and Seafarms is actively partnering with research bodies on improving the quality, health and productivity of farmed marine prawns.

“We are a partner in the Australian Research Council’s Industry Transformative Hub with FRDC, CSIRO, James Cook University and the Australian Genome Research Facility, and this research is going to have a significant flow-on benefit to the whole sector,” he says.

“For example, they have now mapped the entire transcriptome (the genes expressed in different tissue) of the Black Tiger Prawn and are well on the way to mapping the entire genome (the whole DNA set). This will be a major scientific resource.”

Chris Mitchell says multi-government support has been critical to the venture reaching its ‘ready-to-roll’ stage.

Marine aquaculture expands

In addition to land-based aquaculture, the Western Australian and Northern Territory governments are also preparing the foundations to support new developments in marine environments.

The WA Government has introduced dedicated aquaculture development zones off its mid-west coast and in the Kimberley to stimulate the development of large-scale aquaculture.

The state’s aquaculture strategy, released in 2017, identifies initiatives needed to grow the industry. This includes the recently commissioned 3000-hectare Mid-West Aquaculture Development Zone in open water between Geraldton and the southern part of the Abrolhos Islands group. The zone comprises a northern area of 2200 hectares and a southern area of 800 hectares just north of several existing aquaculture licence areas.The WA Government says the development zones provide ‘investment ready’ platforms for setting up large-scale commercial aquaculture operations. The sites have been chosen because of their deep, well-mixed water and large areas of a sandy benthic environment suitable for finfish aquaculture. Geraldton also provides ready access to support infrastructure, including road and airfreight services.

Aquaculture production systems will be in the form of floating sea cages, which use circular flotation rings to support nets that contain the fish being cultured. External nets on the cages exclude predators and minimise the risk of any adverse impacts on marine mammals, such as sea lions. These systems are usually set within a grid pattern and anchored to the seabed.

The WA aquaculture industry, excluding pearling, currently generates $15 million per year in economic value. The state government says its new development zones are aimed at lifting this figure to more than $600 million per year within the next decade.

The total allowable annual production of finfish inside the mid-west zone is set to a maximum biomass (weight of fish in the water) that would equate to an annual production or yield of 48,000 tonnes.

For the species most likely to be farmed, Yellowtail Kingfish (Seriola lalandi), this computes to an economic value of about $400 million. See FISH article Yellowtail Kingfish growing availability for consumers.

The state government expects a further $200 million per year to be generated by the Kimberley Aquaculture Development Zone in Cone Bay at the northern end of King Sound, about 215 kilometres north-east of Broome.

Cone Bay is a proven location for the culture of Barramundi (Lates calcarifer). The tidal influence creates substantial water flow through the sea cages in which the fish are grown, allowing for a high level of productivity with a low environmental impact.

The creation of the zone involved environmental assessment of the whole zone under the WA Environmental Protection Act 1986. A key environmental feature is the high rate of water exchange able to dilute nutrients, which is supported by strict management controls and environmental monitoring.

Northern Territory

The Northern Territory Government has not gone down the same development zones pathway as WA and SA, but it has been actively supporting aquaculture since 1988 when it constructed the Darwin Aquaculture Centre.

The centre was initially established to research and support the development of the Barramundi industry. But over the years it has helped to develop and improve hatchery techniques for Barramundi, Golden Snapper (Lutjanus johnii), Barramundi Cod (Chromileptes altivelis), mud crabs (Scylla spp.) and giant clams (Tridacna squamosa), and now has a strong focus on native rock oysters (such as Saccostrea echinata). The aim of the oyster program is to improve hatchery techniques and to develop oyster farms in regional communities.

The centre also leases space to private companies to help them develop their business and undertake research. Current private R&D includes Barramundi, Pearl Oysters (Pinctada spp.), sea cucumbers (such as Holothuria fuscogilva) and some aquarium species.

More information

Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development – Fisheries

NT Department of Primary Industry and Resources – Aquaculture research and development