A deeper understanding of societal support can provide the fishing and aquaculture industry with a greater chance of achieving the outcomes they want

By Annabel Boyer and Gio Braidotti

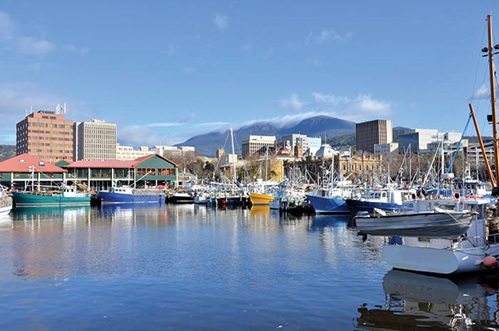

Fishing boats in Hobart harbour.

Fishing boats in Hobart harbour.Photo: Shutterstock

If having the support of your community could be made to formula, what would the ingredients be? A pinch of visibility, a dash of positive media coverage and half a cup of social capital, perhaps?

Unsurprisingly, the answer is not that simple and while a formula would be nice, in reality the answer is rather more complicated. Instead of prescribing a formula, a recently completed FRDC-funded project, ‘Determinants of socially-supported wild-catch fisheries and aquaculture in Australia’, has sought to broaden the understanding of what securing societal support – or as many in the fishing and aquaculture industry would understand it, social licence to operate – really entails.

Researcher Karen Alexander says the aim was not to prescribe what people should or shouldn’t do. “Rather, it is very much about providing the building blocks for a better understanding of the basis of societal support,” she says.

The project was undertaken by marine social scientists Karen Alexander from the Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies (IMAS) at the University of Tasmania and Kirsten Abernethy of Sea Change Consulting in Port Fairy, Victoria.

It was commissioned as part of the FRDC’s Human Dimensions Research (HDR) Subprogram, which oversees the inclusion of social and economic dimensions for all FRDC research proposals, basically broadening the context in which problems are defined and solved.

Marine social scientist Emily Ogier, who is based at the University of Tasmania and who coordinates the HDR Subprogram, says the project will allow for gaps and issues to be more effectively identified, providing a clearer pathway for research investment when tackling what are often wickedly complex issues.

“Identifying the determinants is a pivotal moment for the subprogram,” she says. “It means we can be more systematic about what RD&E we invest in to address declining societal support at a time when fisheries and aquaculture are making greater efforts to be more sustainable.”

Influencing factors

Researches Kirsten Abernethy and Karen Alexander

Researches Kirsten Abernethy and Karen AlexanderIn order to identify common factors or determinants, the researchers conducted a comparison of case studies that demonstrated societal support, or the loss of it – two of which were representative of wild-catch fisheries and two which represented aquaculture.

While there were differences between wild-catch fisheries and aquaculture, Karen Alexander says that the huge number of commonalities across all four case studies was crucial to the identification of viable determinants. “The fact so many similarities came up across four case studies is one of the core strengths of this study,” she says.

Out of this process the researchers identified 16 influencing factors or determinants, which were then combined into the following groups:

- the behaviours of the people working in and representing the fishery or aquaculture farms;

- how industry builds trust with groups they need support from;

- the ability of industry to have influence over how they are perceived; and

- the context or situation they are operating in.

The research revealed some of the complexity involved in achieving societal support and why it is difficult to take a prescriptive, one-size-fits-all approach. For example, researcher Kirsten Abernethy says it is important to recognise that societal support is dynamic. “It is not something that you simply have or don’t have. Some groups of people will support a fishery or aquaculture business and others won’t, and their level of support can waver and change over time.”

The project also revealed that building societal support takes time, is difficult to build in times of crisis and can be lost quickly.

The context for every fishery and aquaculture farm also varies and often there may be parts of a situation that are beyond the control of an operator or business. This could include politics or past experiences with fishing and aquaculture. But Karen Alexander says even in these challenging circumstances, there may be some action that can still be taken.

One solution is, where possible, to call on relationships with stakeholders (including potential adversaries) that have been developed genuinely, over a long period of time. Strong relationships were found to have cascading effects, with stakeholders then spreading positive stories about the fishery or aquaculture activity.

Controlling perceptions

Strong relationships can also be an important tool in relation to how an industry or business is perceived. Kirsten Abernethy says for wild-catch fisheries, actually seeing how the industry fishes, as well as the responsible nature of fishing methods, were identified as being important for maintaining a connection to the local community and gaining its support. Otherwise the fishery is invisible.

On the other hand, the research found that for fish farms, sometimes considered “a blight on the landscape”, this kind of physical visibility can be detrimental to building support.

What is clear from these contradictory examples is that fishing and aquaculture operators need to understand the mechanisms that influence how they are viewed and take control of that space. In the same vein, being sustainable or having a great local product is often not enough to build support, says Kirsten Abernethy.

“A fishery or aquaculture operation has to actively promote its sustainability and its products, whether that is through the media or directly with stakeholder groups, to make a difference in the level of support.

“It’s ultimately about building trust, not just as an individual operator or business, but also as an industry,” Karen Alexander says. “Being honest, transparent and reliable is really important.”

From problems to solutions

From here on, the HDR Subprogram steering committee, which includes eight fisheries and social science experts, will work to build the determinants into future FRDC projects.

Emily Ogier says, looking forward, the subprogram will make the research outcomes accessible to the industry in the form of a self-assessment checklist, which will be refined and tested with industry groups before being formally published. The goal is to help industry participants self-diagnose and understand where they find themselves in relation to societal support.

“We want to move beyond identifying problems and start having positive impacts on outcomes,” she says, “with a range of solutions available to better support people in fisheries.”

Already in the pipeline is a new project about how to evaluate community engagement as it takes a pragmatic look at how support in the community can be improved.

The FRDC has created a dedicated Building Community Trust webpage that provides access to tools and resources to help Australian fisheries and aquaculture operators take action to improve levels of societal support. This includes resources developed by the FRDC and other stakeholders.

Visit Building Community Trust

What is ‘societal support’ for fisheries and aquaculture?

Researchers involved in the project ‘Determinants of socially-supported wild-catch fisheries and aquaculture in Australia’ drew on expert advice and published works across diverse sectors to develop the following working definition of ‘societal support’.

Societal support is a state of acceptance, approval or assistance for fisheries and aquaculture activities granted by stakeholder groups. It is located on a gradient from a low to high level of support.

More specifically, societal support is:

- rooted in the beliefs, perceptions and opinions of stakeholders about a fishery or aquaculture activity;

- perceived differently by separate stakeholder groups, and these groups can grant varying levels of support for a fishery or aquaculture activity;

- not necessarily consistent across geographical scales, and may differ at local, regional and national scales;

- dynamic and changes over time as beliefs, perceptions and opinions are subject to change. Societal support can be slow to gain but lost quickly; and

- determined by the:

- context that surrounds the fishery or aquaculture activity and the external circumstances at the time;

- behaviours, practices and actions of the people within the fishery or aquaculture operation while fishing or farming;

- building of trusting relationships and meaningful engagement with stakeholder groups; and

- ability of the people within the fishery or aquaculture operation to have influence with stakeholder groups.

FRDC RESEARCH CODE: 2017-158

More information

Karen Alexander

karen.alexander@utas.edu.au

Kirsten Abernethy

kirsten.abernethy@gmail.com

Emily Ogier

emily.ogier@utas.edu.au