Preparation that includes both emergency beacons on vessels and weather-related risk management training is highlighted in a new report on safety for commercial fishers

By Catherine Norwood

Photo: Shutterstock

Photo: Shutterstock

Emergency beacons are essential to safety at sea, but back-up monitoring systems and improved training, including a better understanding of weather terminology, could improve the likelihood of fishers coming home safely.

These are among the recommendations from fisheries consultant Geoff Diver in his report Identifying electronic platforms to increase safety at sea in the Australian commercial fishing fleet.

Funded by the FRDC, the investigation had its genesis in the loss of life at sea in the Australian fishing industry, in particular the FV Dianne, lost in Queensland in 2017 and the FV Returner, lost in Western Australia in 2015. A total of nine people died in these two incidents.

Geoff Diver

Geoff DiverConsulting marine scientist,

Diversity Sustainable Development

Geoff Diver says some family members of the crew who died have since advocated for the use of vessel monitoring systems (VMS) as an emergency alert alternative to mandatory emergency position indicating radio beacons (EPIRBs). Both the Dianne and the Returner were fitted with EPIRBs, but neither was triggered as the vessels foundered.

Despite this, his research shows that EPIRBs remain the best emergency alert system, particularly with new regulations introduced in 2018 that require relevant vessels to fit float-free EPIRBs by 2020. These are automatically triggered at depths of two metres of water, unlike the previous model, which needed to be activated manually. EPIRBs are connected directly via satellite to search and rescue authorities, which respond immediately when an alert is triggered.

Back-up systems

VMS systems and automatic identification systems (AIS) are required by some fisheries managers to monitor fishing activity. Their signal does not connect directly to emergency services, but goes to a third party, the authority or monitoring agency.

VMS and AIS signals may not be continuously monitored, which could lead to delays between signals being lost and action being taken to investigate. In the case of the Returner, in WA, all forms of electronic signals had been lost for five days before a search was launched.

For this reason, Geoff Diver says, VMS or AIS are less suitable as a primary distress signal. However, they could be a valuable back-up system to help locate vessels more quickly in emergency events.

He says the loss of a VMS or AIS signal does not immediately represent an emergency. A vessel may have temporarily lost power, or it could be in dock for repairs, or for the off-season.

However, an alert that identified the loss of a signal sent to the management agencies could then allow services such as the water police to be notified and to track down a vessel, ruling out an emergency.

He says this approach could work for all fisheries management agencies that use VMS or AIS tracking. However, there are also resourcing and data privacy issues that management agencies would need to consider. In the case of AIS, there is no ongoing formal monitoring of these signals.

His recommendations also include improved training for the crew on vessels, including induction for new crew and passengers on the location of all safety equipment, including EPIRBs, and how and when to use the equipment.

Weather alerts

Unfavourable weather conditions were identified as contributing to the loss of both the Dianne and the Returner, and Geoff Diver has included several recommendations on this issue.

He was assisted by Lucie Blom from the Bureau of Meteorology’s (BOM) Weather and Marine Forecast Services, who says the BOM is keen to help people make better use of the information it has available and to work with the fishing sector to improve its services. These include:

- coastal waters forecasts and wind warnings;

- MetEye detailed graphical forecasts;

- tidal predictions;

- sea temperature and currents;

- interactive weather and wave maps;

- high sea forecasts and warnings; and

- MarineLite, a marine forecast and warning webpage tailored for use in offshore areas with low bandwidth.

These services are provided via digital channels, as well as on satellite and marine radio.

Lucie Blom says the BOM works closely with the Australian Maritime Safety Authority AMSA to improve access to and use of marine weather services. This includes attending AMSA’s Domestic Commercial Vessel and Fishing Industry Advisory Council meetings.

Among recommendations in Geoff Diver’s report is continued liaison with the Australian fishing industry, AMSA and the BOM to develop a system for communicating information about rapidly deteriorating, localised weather events.

Lucie Blom says the BOM works continually to improve weather services. However, it also wants to help mariners be better prepared by making greater use of services already available.

Improving knowledge about how to use weather information in decision-making will allow skippers to avoid dangerous conditions when possible, and to be better prepared if conditions do deteriorate.

This could include incorporating BOM services into formal weather risk management plans for specific vessels.

Other weather-related recommendations in the report include:

- enhancing training packages such as SeSAFE to understand the weather terminology used in forecasts and warnings;

- distributing the information packages available on the BOM’s website outlining the relevant services for mariners and how to use them;

- developing weather-risk matrixes that fishing operations on shore and at sea can use to make weather-related operating decisions; and

- allowing all crew members to contribute to decisions if there are concerns with weather and sea conditions while at sea.

Update your details

The owners of Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacons (EPIRB) are urged to review and update the contact details for their beacon to ensure they are correct.

Visit the AMSA website.

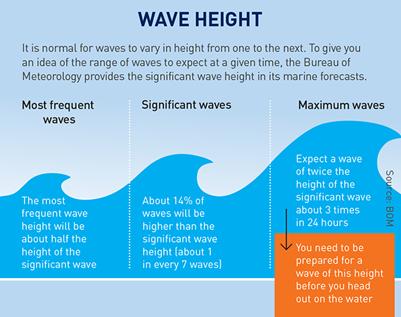

Understanding wave terminology

The language used in weather forecasting may seem relatively general, but in practice, the terminology has clearly defined meanings that can be applied to evaluate a specific vessel’s ability to remain at sea.

The Bureau of Meteorology provides forecasts of wave (sea and swell) heights in metres. Wave heights describe the average height of the highest third of the waves (defined as the significant wave height – see diagram above). It is measured by the height difference between the wave crest and the preceding wave trough.

KING or ROGUE WAVES are waves greater than twice the total wave height. One of the ways these very large waves occur is when ocean currents run opposite to the prevailing sea and swell, and waves overrun each other.

This generates steep and dangerous seas.

SEA WAVES are generated by the local prevailing wind. Their height depends on the length of time and speed the wind has been blowing, the fetch (the distance the wind has blown over the water), and the water depth. They may also be referred to as seas in marine text forecasts and wind waves in map displays.

SIGNIFICANT WAVE HEIGHT is the statistical basis for all wave heights presented in text forecasts and map displays. Wave heights vary over time. The statistical definition is calculated as the average height of the highest one third of the waves experienced over time.

SWELL WAVES are the regular, longer-period waves generated by distant weather systems. They may travel over thousands of kilometres. There may be several sets of swell waves travelling in different directions, causing crossing swells and a confused sea state. Crossing swells may make boat handling more difficult and pose heightened risk on ocean bars. There may be swell present even if the wind is calm and there are no sea waves.

TOTAL WAVE HEIGHT is the combined height of the sea and the swell that mariners experience on open water. It may also be referred to as the combined sea and swell or significant wave height. The probable maximum wave height can be up to twice the total wave height.

WAVE LENGTH is the average distance between crests (or troughs) of waves.

WAVE PERIOD and SWELL PERIOD is the average time between crests (or troughs) of waves. The larger the time difference, the greater the amount of energy associated with the waves or swells.

FRDC Project Code: 2018-106

More information

Geoff Diver, 0418 266 065

geoffdiver@iinet.net.au

Lucie Blom

lucie.blom@bom.gov.au