The fifth edition of the Status of Australian Fish Stocks, launched on World Oceans Day, 8 June 2021, marks a decade of expanded national assessments of Australia’s fisheries

Words Annabel Boyer Illustrations efishalbum.com

With its fifth edition completed, the Status of Australian Fish Stocks (SAFS) Reports mark a decade of assessments that provide a national overview on the health of Australia’s fisheries. The fifth edition is the largest assessment of Australia’s fish stocks ever completed and a mighty achievement of coordination and collaboration by scientists and agencies around the country. Their size and scope, too, puts Australia ahead of the game globally compared to similar reports produced overseas.

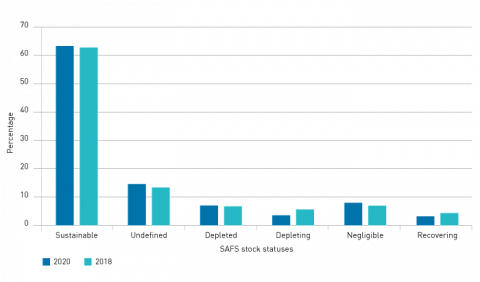

The latest edition of SAFS Reports assess 477 stocks of 148 of Australia’s fish species, adding 71 stocks of 25 species to the 2018 reports. The SAFS framework uses stock status categories of sustainable, depleting, depleted, recovering, undefined and negligible to give an indication of the sustainability of each fish stock. The SAFS Reports not only provide the opportunity to highlight sustainable species, but also to understand where there are issues such as data gaps or the need for management intervention or additional research to resolve status concerns or uncertainty.

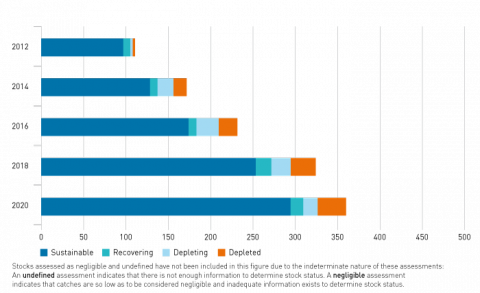

With greatly expanded coverage since the original SAFS Reports of 2012, the fifth edition demonstrates a trend towards sustainability (see Figure 3).

Among the highlights in the new reports are the improved status of Spanner Crab (Ranina ranina) (east coast biological stock), which has transitioned from depleting to sustainable, and Yellowtail Kingfish (Seriola lalandi) (eastern Australia biological stock), which has transitioned from undefined to sustainable.

A result of adding species and stocks to the reports is an increase in the proportion that have an ‘undefined’ status. This is because these stocks have limited data, making an assessment very difficult. This highlights the need to find out more about the species and stock, as well as increase the level of data collected relating to its harvest, whether commercial, recreational or Indigenous.

In some cases, the latest assessments incorporate new knowledge. For example, the importance of multiple spawning locations for the eastern Australian stocks of Tailor (Pomatomus saltatrix), revealed by recent research, has been recognised. Assessments of tropical snappers (Saddletail Snapper, Crimson Snapper and Goldband Snapper in the Lutjanidae family) also include insights from the analysis of otoliths (fish ear bones) and parasites to understand the stocks to a more refined level.

Blue Morwong, Ruby Snapper, Teraglin and Golden Perch. Illustration: efishalbum.com

New species, new challenges

Several new species included in the latest SAFS Reports (released in 2021) have provided both challenges and novelty to the assessment process, says the FRDC’s SAFS program manager Toby Piddocke.

For instance, two eel species – Longfin Eel (Anguilla reinhardtii) and Southern Shortfin Eel (Anguilla australis) – are both being reported on for the first time.

Eels have an unusual biology: they only spawn once in their life and take a long time to reach maturity. Female Longfin Eels do not reach maturity until they are in their 50s.

They spend most of their lives in rivers or estuaries before heading to the Coral Sea where they spawn before dying. Their young then travel back to the waterways where they spend most of their lives.

“It’s a really unusual biology that throws up a lot of assessment challenges and a lot of jurisdictional particularities, so they are interesting species to report on,” Piddocke says.

Another new species to present some interesting questions for the SAFS Reports is the Longspined Sea Urchin (Centrostephanus rodgersii). This species has moved south from its traditional range as waters have warmed, causing ecological issues.

“This is a really interesting issue from the point of view of SAFS reporting because, in these instances, the removal of urchins is considered necessary to minimise ecological impacts. This can lead to the preference to reduce the biomass to really low levels in those areas.”

The new SAFS Reports also include some species well known to fishers, but which have yet to be formally described by science. Among these is a fish from the tropical Ruby Snapper group, of the genus Etelis.

SAFS authors identified that the species that makes up the largest share of the Ruby Snapper catch is one that has not formally been described by taxonomists. Known as Giant Ruby Snapper, this warm-water species inhabits deep reefs off northern Australia. There is a paper underway to have the species formally described and recognised as Etelis boweni.

Another new species in SAFS that is yet to be formally described by science has previously been referred to as the western stock of the Gloomy Octopus (Octopus tetricus).

For many years it has been recognised that the western species is distinctly different to the Gloomy Octopus found on the east coast of Australia, and so the western species will be included in SAFS as Octopus djinda. The formal naming process is the subject of an FRDC project 2018-178. Djinda means ‘star’ in the Noongar language and has been chosen because it is uniquely Western Australian. Formal acceptance of the name by the scientific community is expected by the end of the year.

Figure 1: Number of species and stocks, 2018 and 2020

|

SAFS 2018 |

SAFS 2020 |

Change |

|

| Number of species | 120 | 148 | +25 new species* |

| Number of stocks | 406 | 477 | +71 new stocks |

* Some species previously reported on as species groups (i.e. two or more species combined into a single reporting unit, such “Australian Salmons”) have been split into distinct species reports for SAFS 2020. These newly separated species complexes are NOT included in the count of new species. A species complex is a group of similar species that are often difficult to differentiate without detailed examination.

More than a rating system

While the changing status of different species understandably grabs the headlines, the national nature of the SAFS Reports as an overview of Australia’s fisheries health has other less obvious, but equally important, benefits.

Piddocke says as well as providing a national overview, the reports give researchers, who otherwise may not be able to work together, the opportunity to collaborate and learn from one another.

“Obviously the product we put out at the end is the reports, and we want people to read those and get value from them. However, the cross-jurisdictional relationships SAFS fosters among fisheries scientists are equally important.”

Piddocke says the benefits of these relationships extend beyond SAFS, with several authors noting that, as a result of participating in SAFS, they are now more likely to pick up the phone and discuss relevant issues with their colleagues in other jurisdictions.

“SAFS also provides a unique national perspective on the status of the stocks it addresses. Fisheries management falls to state, territory and Commonwealth jurisdictions, so the fisheries science tends to be divided the same way. SAFS provides an opportunity to get a higher level perspective across jurisdictions on stock performance and data needs.”

The new SAFS online reporting form is contributing towards greater reporting consistency across jurisdictions and also helps Australia meet obligations to report against the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

Figure 2: Percentage of stocks by category, 2018 and 2020

Figure 3: Trends in sustainability of Australian fish stocks 2012–2020

A consistent framework

The latest edition has seen a big change in how the reports are produced. For the first time, an online authoring form using dropdown menus and tick-box selections was used to standardise terminology for things like fishing methods. “Previously, we’d end up with this huge list of different methods that were all essentially the same,” Piddocke says.

The Northern Territory and Western Australia are already using the SAFS framework for their own jurisdictional assessments, with other jurisdictions assessing how it might work for them. Piddocke says the ultimate goal of the reporting framework is to reduce duplication and increase efficiency.

The SAFS Reports is available at fish.gov.au and as a smartphone app. It includes interactive modelling of trends in the sustainability of Australia’s fish stocks, with users able to select species to see trends from 2012 through to 2020, at fish.gov.au.

What is a ‘Fish Stock’?

A stock is another way of saying population or sub- population. Use of the term fish stock usually implies that the particular population is more or less isolated from other stocks of the same species and hence self-sustaining.The Status of Australian Fish Stocks (SAFS) Reports uses the term ‘stock’ generically for populations of fish defined at any of three levels – biological, management units and populations assessed at the jurisdictional level.A biological stock is a discrete genetic population or a population of fish that is not interacting with other fish populations of the same species. That means this population size can be treated as relatively constant and changes to its structure and size can be measured. It is not always practical to measure an entire biological population, so the unit may be defined in other ways such as who manages it or where it is. A key aim of fisheries management is to ensure that biological stocks are maintained at sustainable levels.

New species included in SAFS Reports 2020

Australian Bonito (Sarda australis)

Barred Javelin (Pomadasys kaakan)

Blue Morwong (Nemadactylus valenciennesi)

Bronze Whaler (Carcharhinus brachyurus)

Brownstripe Snapper (Lutjanus vitta)

Burrowing Blackfish (Actinopyga spinea)

Champagne Crab (Hypothalassia acerba)

Cobia (Rachycentron canadum)

Crystal Crab (Chaceon albus)

Eastern Shovelnose Ray (Aptychotrema rostrata)

Golden Perch (Macquaria ambigua)

Greenback Flounder (Rhombosolea tapirina)

Hammer Octopus (Octopus australis)

Longfin Eel (Anguilla reinhardtii)

Longspined Sea Urchin (Centrostephanus rodgersii)

Ocean Sand Crab (Ovalipes australiensis)

Redspot King Prawn (Melicertus longistylus)

Ruby Snapper (Etelis carbunculus and Etelis boweni description pending)

Southern Shortfin Eel (Anguilla australis)

Striped Trumpeter (Latris lineata)

Stripey Snapper (Lutjanus carponotatus)

Teraglin (Atractoscion aequidens)

Trumpeter Whiting (Sillago maculata)

Western Blue Groper (Achoerodus gouldii)

Western Rock Octopus (Octopus djinda, description pending)

Measuring progress

The Status of Australian Fish Stocks (SAFS) Reports brings together available biological, catch and effort information to determine the status of Australia’s key wildcatch fish stocks. As of July 2018, SAFS summary information has been used to inform Australia’s progress against United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 14: Life below water. Target 14.4 is: By 2020, effectively regulate harvesting and end overfishing, illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing and destructive fishing practices and implement science-based management plans, in order to restore fish stocks in the shortest time feasible, at least to levels that can produce maximum sustainable yield as determined by their biological characteristics. The indicator used to assess progress towards this target is 14.4.1: Proportion of fish stocks within biologically sustainable levels.

FRDC RESEARCH CODE 2019-149

More information

Toby Piddocke, FRDC,

toby.piddocke@frdc.com.au