In the wide world of sharks and rays, Australia is doing remarkably well, according to the latest comprehensive national assessment of shark and ray stocks.

The 2023 Australian Shark and Ray Report Card is now complete. It provides a national and international assessment of the stock status of 331 species of sharks and rays in Australian waters.

In this second report card 137 species have been added to the first report released in 2019, making a grand total of 341 species stock assessments (note that some species have more than one stock, such as the Grey Nurse Shark (Carcharias taurus)).

The total number of species recognised has increased due to advances in scientific knowledge, with nine new species added to the list of Australia’s sharks and rays since 2019. Australia is widely recognised as home to the most diverse and distinctive sharks and rays, with approximately a quarter of the species found nowhere else in the world.

“Overall, Australia’s sharks and rays are in relatively good condition, and Australia’s management of these species is world-leading,” says Professor Colin Simpfendorfer, an international shark expert and lead researcher on the FRDC-funded project (FRDC 2020-105).

The Shark and Ray Report Card uses the criteria established by FRDC’s Status of Australian Fish Stocks (SAFS) Reports for assessments, with its results integrated into the upcoming SAFS update.

Key findings of stocks assessed:

-

68% are Sustainable

-

3% are Recovering

-

4% are Depleting

-

6% are Depleted

-

5% are Undefined (insufficient information)

-

14% are Negligible (little interaction with fisheries)

Colin says, of those stocks assessed as depleted, most are listed as a protected species so they are being actively managed through rebuilding plans and associated legislation, or they are currently being assessed for protection under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act.

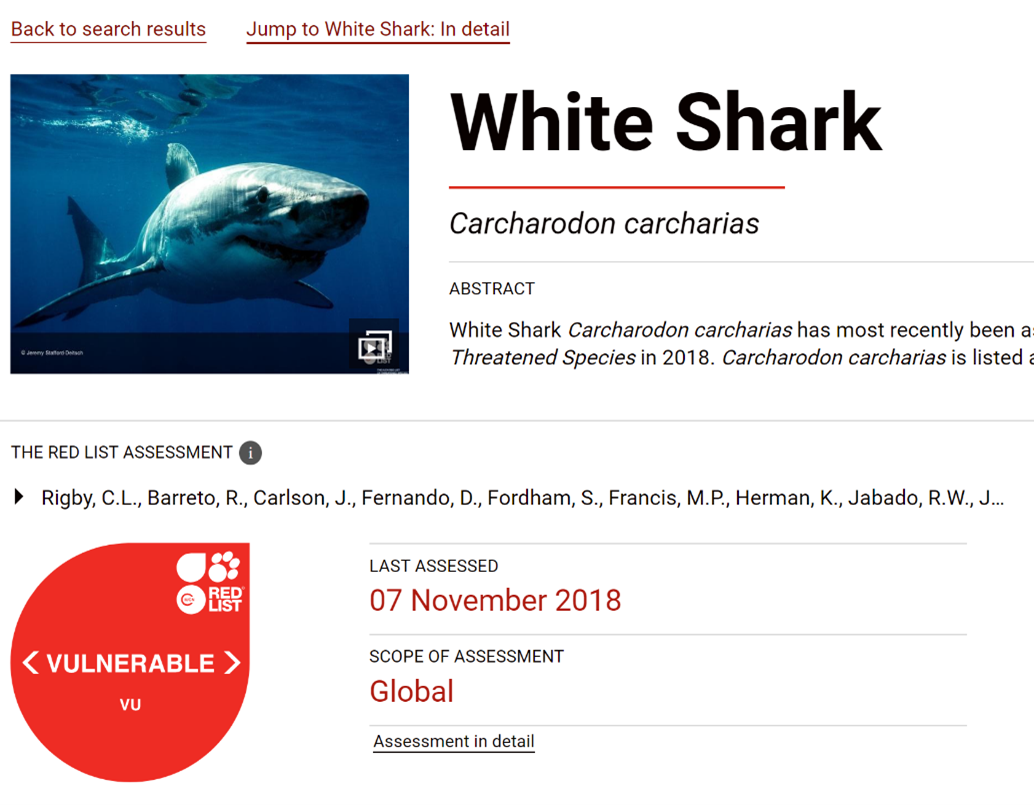

The report card also provides a comparison of Australian stocks against the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species.

“Especially when you compare us to the rest of the world, the proportion of threatened species Australia has is vastly lower than it is for almost any other nation in the world,” says Colin.

“That's not only good management, it’s also low fishing pressure; we don't have the very large intensive fisheries many other nations have.

“Australian management of sharks and rays is better than the global average, and it confirms Australia’s role as ‘a global lifeboat’ for several species”

“We still have issues with some species, and the report identifies 11% are threatened under the IUCN Red List. The good news is that we know what they are. We know what the issues are with most of them and we're already working towards solving them."

Identifying gaps for further work

While the report card shows Australia is doing well, Colin highlights its value in providing a comprehensive resource for all those interested in the future of sharks and rays. This includes identifying gaps in the available information and highlights where researchers and managers can focus their efforts. It also highlights where more information on species in the ‘undefined’ category most of which are deep-sea species, is needed.

Colin also highlights the need for training for fisheries observers and fishers to help identify species, particularly those which are difficult to tell apart at first glance, as this will contribute to future stock assessments.

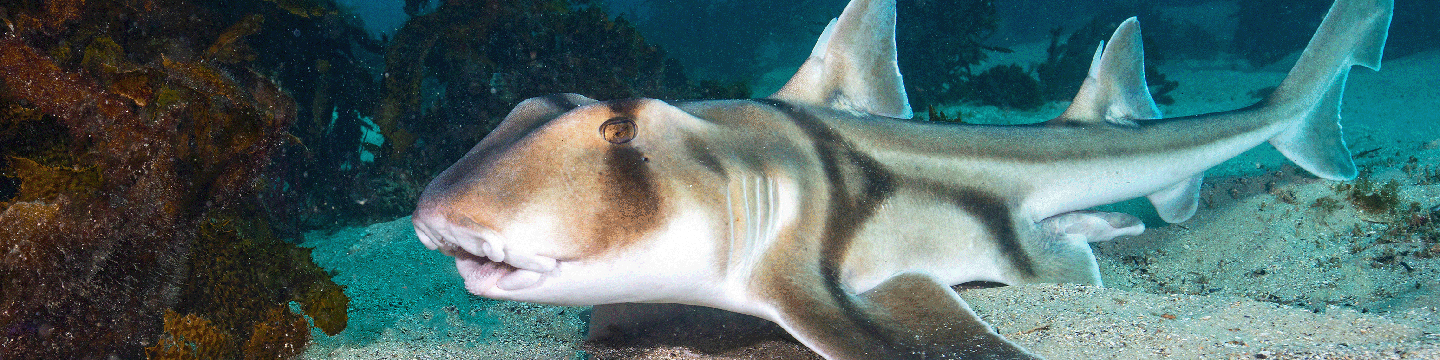

“There’s a group of stingarees that all look very similar and generally identified as a ‘group’ that we’re trying to untangle, to make sure we understand the status of the different species in that group and so we can protect them if required,” he said.

A new range of species are also being added to the Convention on International Trade and Endangered Species (CITES) list including sharks, to regulate international trade. Colin says fishers will need to identify sharks to species level for export, which is a small but valuable part of some shark fisheries.

Valuing diversity

With almost 40 years of experience researching sharks and rays, Colin continues to be inspired by these species that he says are among the most diverse group of animals in the ocean world.

“Some of them live maybe five or six years, others live to 100 years or even more, which means you need to manage these stocks quite differently,” he says.

“Sharks and rays probably have the greatest diversity of reproductive modes of any group of vertebrate animals. There are egg layers and there are live bearers. Of the ones that give birth to live young, there are a whole range of different ways that they nourish them.

“Some have placentas like mammals; some baby sharks eat each other in the womb; stingrays produce a form of milk in the uterus that the young absorb. It’s a fascinating group of animals, beyond the big, scary predators that most people think of. The majority of them are mesopredators – in the middle of the food chain.”

Colin says it’s an ongoing challenge to direct attention away from great White Sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) and manta rays to some of the lesser-known species, all of which are included in the latest Shark and Ray Report.

While he doesn’t have a favourite, he does still have a soft spot for one of the species he studied early in his career, Western Australia’s Pencil Shark (Carcharhiniformes Triakidae). His work remains the only source of biological information on the species, despite its wide range from South Africa to Australia and north to Japan.

“It’s quite a boring-looking shark,” says Colin. “However, it’s one of those rarely seen but really quite important animals in the ocean, that we need to identify and protect.”

Related FRDC Projects

2020-105: Development of a Stock Status Report Card for Rays and Sharks