The remarkable story behind the recovery of Southern Bluefin Tuna from an endangered species to a globally sustainable fishery is told in a recently released Australian documentary

By Brad Collis

The combined efforts of Australian science, industry innovation and community education have been showcased in the documentary Life on the line − The story of the Southern Bluefin Tuna, which tells the story of how these highly prized, temperate ocean dwellers were brought back from the brink of commercial extinction.

Produced and narrated by photojournalist and ardent fisher Al McGlashan, the documentary tells of how the Southern Bluefin Tuna (SBT) (Thunnus maccoyii) stocks went into freefall due to overfishing and how the fish was rescued from its near demise. It also explains how the strategies and science that saved the SBT now stand as a sustainability model for fisheries worldwide.

Al McGlashan gives the narration a personal perspective that also resonates with the scientists and fishers – commercial and recreational – who are central to the story: “My father used to tell me about this amazing tuna, but I’d never seen one as a child,” he says.

“It’s long been a dream of mine to tell the story of the SBT, about how the stocks are recovering … and to see fishers appreciating and respecting these athletes of the sea.”

Life on the line provides an engrossing insight into this warm-blooded marine species and its decade-long lifecycle that sees it reaching 200 kilograms and two metres in length by the time it has traversed the Southern Ocean. The film details the commercial pressures that decimated the SBT population and the extraordinary individuals who led its recovery, in the process creating a new, sophisticated industry worth more than $100 million annually in Australia alone.

The documentary was funded by the Australian Government through the Australian Fisheries Management Authority (AFMA) and the FRDC, both of which were instrumental in the SBT success story, along with the CSIRO.

Two technological developments were particularly critical in the recovery of the species. First, Australia’s SBT fishers took the lead in developing a new approach, learning how to catch juvenile fish to grow them out in ocean pens off the coast of Port Lincoln, South Australia. The fishers became farmers.

The second was the advent of genetic ‘fingerprinting’ and satellite tagging for population monitoring and management. Given SBT begin life in waters off Java and north-west Australia before they traverse the Southern Ocean beneath Australia and South Africa, these technologies remain crucial for setting evidence-based quotas that are now respected by all countries and markets with commercial interests in the species.

The beginning

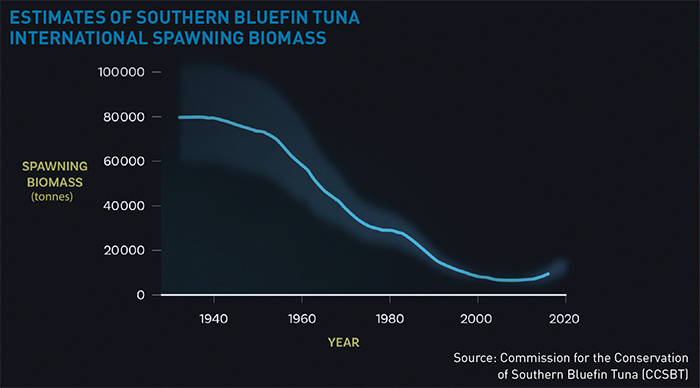

The SBT story starts in the early 1980s when the species’ red meat was so prized in markets such as Japan – which consumes 80 per cent of the global catch – that a single fish could fetch tens of thousands of dollars. But this boom time for fishers was followed quickly by diminishing catches. By the time the market was peaking, the SBT population was already in terminal decline.

“By the early 1990s, SBT was on the road to extinction,” says Al McGlashan.

At the time, Japan was still catching more than 40,000 tonnes of SBT a year and Australia about 21,000 tonnes, but the population was estimated to be at barely five per cent of 1960s levels.

Something drastic needed to be done and, according to Al McGlashan, AFMA CEO Glenn Hurry was the one to do it, taking a leading role in setting up the Commission for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna.

The commission allowed the three main catching countries, Japan, Australia and New Zealand, to manage the fishery cooperatively.

Data gathering

Without access to any reliable population data, the three countries estimated that a combined annual catch of 11,750 tonnes would allow stocks to recover. Instead, stocks kept falling. By 2004, the situation was critical and perplexing. A US scientist on the conservation commission said it was clear that the quota was not being adhered to.

Confident in the records being kept by Australian fishers, Glenn Hurry arranged for a team led by Southern Australian Bluefin Tuna Association CEO Brian Jeffriess to visit Japan and calculate how much SBT tuna was being sold.

It was soon apparent there was far more fish on the market than was possible under the quota. When the Japanese denied any overcatching, Glenn Hurry offered to foot the bill – $1 million – for Japan to undertake a comprehensive audit. This found the overcatch in Japan to be as high as 178,000 tonnes over the previous two decades.

For Glenn Hurry, the numbers finally started to make sense and they gave fisheries management data that would allow a scientifically based approach to getting the fishery back to a biologically safe level. Critically, he resisted calls to close the fishery, arguing it needed to be kept open to help fund the necessary research.

“We needed to save the fishery to save the fish,” he says.

This also gave the Port Lincoln-based industry the impetus to rethink its entire operation.

“Nothing focuses the mind like receivership,” says Brian Jeffriess.

Collaborative action

The answer the industry came up with was tuna farming, but no one had ever before attempted to ‘ranch’ wild SBT, an apex ocean predator that has to swim its body length every three seconds to stay alive.

The technique developed was to net juvenile tuna in the ocean, then tow them to inshore pens that are large enough and deep enough to allow the young fish to grow under free-range conditions until ready for harvest. Feeding the penned tuna also led to the development of a massive industry supplying locally caught pilchards, the tuna’s natural food in the wild.

Port Lincoln fisher Tony Santic, principal of Tony’s Tuna International Pty Ltd, says the endeavour succeeded where similar ‘farm’ efforts overseas have not because everyone saw the need to be innovative and to work together.

The need to collaborate is one lesson learned, says Al McGlashan, and the other is the critical role of science. The documentary highlights, in particular, the research undertaken by the CSIRO in Hobart and by the Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies (IMAS) at the University of Tasmania.

Principal CSIRO research scientist Richard Hillary has been monitoring SBT populations through an advanced mark and recapture model. This uses each tuna’s unique genetic ‘fingerprint’ for an identify-and-release program.

The technology takes advantage of high-throughput robotic DNA sampling adapted from human diagnostics and is able to compile a database of tens of thousands of fish. This is supplemented by satellite tagging of a representative sample of fish as they round the south-east corner of Australia.

The resulting population database enables an evidence-based approach to setting quotas. It has also facilitated a community education push that has seen recreational SBT fishers, too, become a part of the overall SBT research and management effort.

Principal investigator with IMAS Sean Tracey says recreational fishers and game fishing operators have become champions of SBT, with some also being involved in tagging as part of an increased emphasis on catch-and-release. With the recreational sector operating in different areas to commercial fishers, this wider community engagement has significantly extended researchers’ coverage.

Al McGlashan believes the SBT recovery is an inspiring story that needs to be better known in the wider community for the lessons learned and for creating a shared sense of responsibility towards what he describes as an iconic marine species.

Importantly, Glenn Hurry notes the SBT recovery in Australian waters is being mirrored in other international marine jurisdictions, as the SBT community is a worldwide one.

SBT is officially assessed as ‘recovering’ in the Status of Australian Fish Stocks Reports (SAFS).

To view the movie, click here.

FRDC RESEARCH CODE: 2017-098

More information

Al McGlashan

al@almcglashan.com