Camera technology lights the way towards improved stock assessments as researcher Tony Courtney discovers in his search for ways to better understand Queensland’s Scallop fishery

Sea scallops in buckets.

Sea scallops in buckets.Photo: NOAA Fisheries

As the adage goes, counting fish is like counting trees, except that they are invisible and they keep on moving. While fisheries scientists have a variety of tools at their disposal to help solve the problem, the space is always ripe for change.

Earlier this year, researcher Tony Courtney visited the US to take part in data collection activities on board the research vessel the RV Hugh R Sharp. He is working on FRDC-funded research to understand Ballot’s Saucer Scallop mortality rates in Queensland’s East Coast Otter Trawl Fishery (FRDC project 2017-048).

The purpose of the voyage was to survey Atlantic Sea Scallops (Placopecten magellanicus) off the coast of Maine and Massachusetts.

The Atlantic Sea Scallop fishery extends across several US north-east states and into Canadian waters and is one of the two most valuable commercial fisheries in the US, valued at about US$480 million (A$678 million) annually.

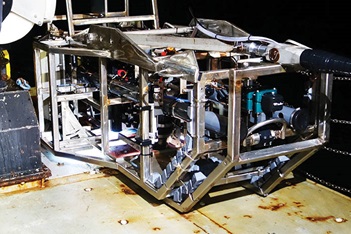

For Tony Courtney the trip was an opportunity to observe and learn about the survey methods used on board the RV Hugh R Sharp, in particular HabCam, a habitat-mapping camera system that photographs the sea floor, capturing the various species living on it. The technology is used by the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) for their scallop stock assessment and may also be applicable in some Australian scallop fisheries.

Tony joined the RV Hugh R Sharp for the last six days of its 32-day survey when it came to port at Woods Hole to refuel. It is a 44.5-metre state-of-the-art research that operates as part of the University-National Oceanographic Laboratory System (a network of research bodies formed to make best use of research vessels and resources across the US), and is based at the University of Delaware.

During the survey voyage, the vessel was staffed by a crew of eight and an additional team of 12 scientists, researchers and volunteers focusing on data collection.

The vessel costs about US$16,000 (A$22,593) a day to charter or US$512,000 (A$722,887) for the whole survey; data is collected continuously, 24 hours a day, with crew and research teams working 12-hour shifts.

“The survey is very well organised and the data derived from it are being directly used to assess the stock and make management decisions,” Tony Courtney says.

HabCam technology

NOAA has been conducting scallop dredge surveys for decades, but since 2011 has incorporated the camera-based system called HabCam into its survey design. HabCam takes photographs of the sea floor that are then used to count the number of scallops for stock assessment.

HabCam takes six photographs of the sea floor per second while the vessel travels at about six knots. This equates to two photographs per metre. HabCam is deployed for about 21 of the 32 days and during this time generates about 10 million images of the sea floor.

The voyage included 11 days of dredge sampling. Each dredge sample was deployed on the bottom for 20 minutes, and once brought to the surface, the catch was processed. The number and size of all scallops was recorded, as well as the number and weight of any other species. Data at sea

While NOAA has developed software to automatically process the images to detect and measure scallops, it is not as accurate as a trained human eye. As a result, NOAA still relies on manual annotation of images for the scallop assessment, but only about two per cent (approximately 200,000 images) can be processed by trained scientists, researchers and volunteers to derive the annual abundance estimates.

While this is labour-intensive, trained annotators can process about 1000 images per day. About half the images are processed at sea, with the remainder processed in the laboratory after the survey.

“I was impressed with the skill, knowledge and speed at which NOAA researchers who have participated in previous surveys annotate the images,” Tony Courtney says.

The HabCam Survey produces very large datasets, which has proved to be a significant unanticipated challenge. The system generates two to three terabytes of data daily, about 70 terabytes during the course of an annual survey. For this reason, the system requires a full-time data specialist to track, store, copy and access the images and other data, including sonar, temperature, conductivity, turbidity and oxygen data collected by sensors on the HabCam.

Australian applications

Tony Courtney thinks the Queensland Saucer Scallop fishery may be suitable for a similar towed camera-based survey. That data could be used to derive an index of abundance, which is more accurate than the current trawl survey estimate.

“The methodology also has less impact on the sea floor than the current trawl survey, which is conducted in Queensland,” he says.

The Queensland Saucer Scallop lives on the sea floor and has limited swimming ability; it is similar to the Atlantic Sea Scallop, although the North American species is slower-growing and lives longer.

As much of the Queensland fishery occurs in waters of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park, Tony Courtney says a camera-based approach may have potential as an additional method for monitoring the benthic ecosystems in the marine park. It may also have application in other fisheries, such as the WA Saucer Scallop fishery, which is the same species as that fished in Queensland.

Although implementation in Australia would require significant funding, Tony Courtney believes that the range of potential applications means that this could be supported by a broad user base.

“The trip was one of the most useful and stimulating experiences I have had,” he says. “Since my return I have been trialling different towed cameras, an automated underwater vehicle and remotely operated vehicles to see how suitable these may be at photographing scallops.”

Tony Courtney

Tony CourtneyResearcher.

Photo captions (from top right)

Releasing the dredge sampling.

The HabCam equipment.

Staff monitoring HabCam images.

An Atlantic Sea Scallop.

Photos: Tony Courtney

FRDC Research Code: 2017-048

More information

Tony Courtney, tony.courtney@daf.qld.gov.au