Molecular analysis is proving vital in revealing the diversity of Queensland’s native oysters as the development of a new aquaculture initiative accelerates

By Catherine Norwood

Carmel McDougall surveyed oyster reefs along the Queensland coast to establish the diversity of species native to the state.

Photo: Nikolina Nenadic

A survey of Queensland’s intertidal oysters has identified surprising diversity, finding 14 distinct species, including one entirely new discovery, and another exotic species reported in Australian waters for the first time.

It has also found five distinct species of tropical oysters, at least one of which is a favoured candidate for new aquaculture initiatives in the state.

The Queensland Government and the FRDC funded the survey and analysis of intertidal oysters, which was led by Griffith University and the Queensland Museum. The three-year project is part of a larger research program funded through an Advance Queensland Fellowship to help reinvigorate Queensland’s once-substantial oyster industry.

Griffith University molecular biologist and mollusc specialist Carmel McDougall led the oyster survey. Sampling was carried out in 2018 and 2019, with assistance from Queensland oyster growers.

She used DNA analysis to identify species, using the international GenBank database as a reference, and says she was surprised by the diversity the survey revealed. “The number of different species we found was much higher than we anticipated. It is difficult to distinguish many of them visually, because they do look pretty similar,” she says. “But the DNA analysis is unambiguous in its results.”

DNA identification

The 14 species identified includes the well-known Sydney Rock Oyster (Saccostrea glomerata), Blacklip Oyster (Saccostrea lineage J), Spiny Rock Oyster (Saccostrea lineage B) and Milky Oyster (Saccostrea scyphophilla – which appears to be two distinct species).

Of the remaining species, one is an entirely new discovery, which is yet to be officially named. Another is Black Scar Oyster (Magallana bilineata), known to be exotic to Australia and discovered for the first time in Australian waters during the survey (see breakout story).

The DNA analysis revealed that Queensland hosts eight species within the Saccostrea genus. While the Sydney Rock Oyster has been widely recognised, Carmel McDougall says it seems likely the Milky Oyster and the Blacklip Oyster have previously been grouped together as Saccostrea cucullata, which is now recognised as a ‘superspecies’.

Australian researchers have been cautious about naming the exact species within this group, preferring instead – at least for the moment – to use the term ‘lineage’ to distinguish between them. This is an established practice in scientific circles.

The use of lineage to distinguish species reflects ongoing debate in the scientific community about the genetic heritage of different species based on DNA analysis, which can conflict with historically assigned scientific names.

Those identified in Queensland are Saccostrea lineage B, F, G, I and J. Other lineages are found elsewhere in the Indo-Pacific region, including lineage A, which is native to Western Australia and is the focus of aquaculture trials there.

Carmel McDougall says applying the right taxonomic naming is critical to the progress of the aquaculture sector because the names are incorporated into the legislation that allows aquaculture of a particular species to occur. It also restricts the movement of genetic material, from hatchery to farm or from one growing region to another, to address biosecurity risks. This can restrict business development.

The oyster survey has mapped the natural distribution of each species within the survey area, which stretched along 2000 kilometres of Queensland coastline from Moreton Bay north to Cooktown. Range information is included in the new online publication produced as part of the project, the Guide to Queensland’s intertidal oysters, which provides identifying images and descriptions.

Advancing aquaculture

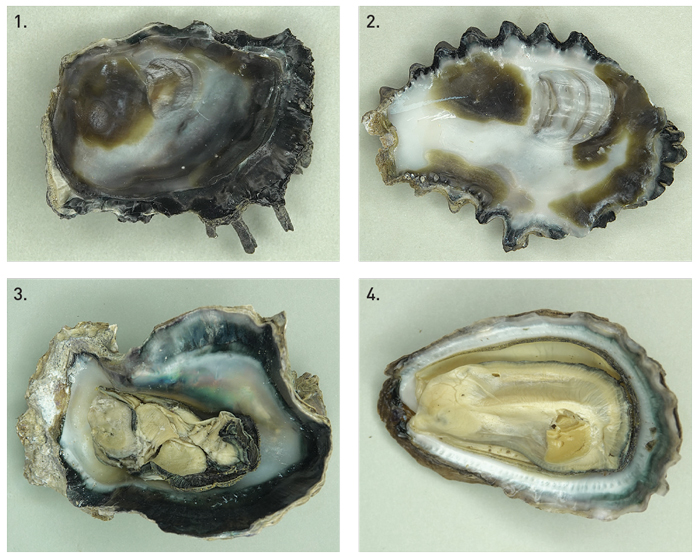

Some of the 14 species identified include:

1. Spiny Rock Oyster, 2. Milky Oyster,

3. Blacklip Oyster, 4. Saccostrea lineage F

Photo: Griffith University

In Queensland, permission to grow a particular oyster will only be granted within the natural range of that species, to prevent ‘genetic pollution’ of local populations. This makes species identification and distribution mapping essential. Oysters are also likely to perform better within their preferred natural environmental range, says Carmel McDougall.

Blacklip Oysters (lineage J) are the favoured candidate for aquaculture because they grow quickly, to a large size, and have good consumer acceptance. They are also tolerant of fluctuating conditions in their growing environments, which is reflected in their wide distribution north of Stanage Bay.

To date, Queensland’s aquaculture efforts have focused on Saccostrea lineage J, including an established farm at Bowen in northern Queensland. The Darwin Aquaculture Centre in the Northern Territory is also culturing this species for grow-out trials, working with Indigenous communities. However, poor larval survival in culture and poor settlement rates have proven a barrier to production.

Using lineage J as the focus for further work, Carmel McDougall has developed a suite of molecular resources to adapt molecular techniques developed for Sydney Rock Oysters for use on Blacklip Oyster larvae.

This includes identifying markers for genetic traits that might help to improve production and accelerate hatchery processes, such as the readiness of spawn to settle and disease resistance.

She says subtle genetic differences in nervous system genes between the two species indicate further research into settlement conditions specific to Blacklip Oysters may be needed.

While the settlement of Sydney Rock Oyster larvae can be chemically triggered, Blacklip Oyster larvae did not show the same response despite their general genetic similarities.

Larval settlement remains an important focus of hatchery efforts, with best settlement rates reported at 10 per cent, compared to between 40 and 70 per cent for Sydney Rock Oysters. Hatchery trials led by Sam Nowland at the Darwin Aquaculture Centre have provided someimprovement in Blacklip Oyster settlement rates.

Based on her molecular analysis, Carmel McDougall suggests further research to identify the influence of factors such as water salinity, temperature and larval density may help identify how to further improve this. Hatchery and grow-out trials comparing Sacosstrea lineage B, G and J would also be valuable in assessing the potential of all three species as aquaculture candidates, she says.

Food safety

The FRDC also has several other projects underway to support the development of tropical oyster aquaculture in northern Australia.

One project (2020-021) will adapt the Australian Shellfish Quality Assurance Program to include tropical oysters, providing guidance to northern growers on shellfish food safety and risk management.

The quality assurance program provides guidance on bivalve food safety across Australia, developed largely through the knowledge and experience of the temperate edible oyster industry and adaptation of international guidelines.

Tropical Australia has unique challenges: temperature, environment, limited infrastructure and remoteness. The emerging tropical oyster industry requires an assessment of the risks and options to manage the sale of an initial small-scale production of farmed bivalve shellfish from northern Australia.

Adapting the program for northern conditions will involve developing recommendations on appropriate growing area classification systems (based on water or meat results, or a mix of both), monitoring and risk management protocols for oyster farming in tropical Australian environments and remote contexts. Potential models for a shellfish food safety program in tropical Australian conditions will also be developed.

Another project (2020-043) will develop cold chain transport and storage guidelines for tropical rock oysters to maintain food safety.

The focus of this project is on the management of naturally occurring Vibrio bacteria found in warm waters, which can affect tropical rock oysters and result in food poisoning. This work will also support remote and Indigenous communities in the development of new aquaculture businesses, providing advice on cooling and handling requirements to prevent bacterial growth and maintain food safety.

Carmel McDougall

Photo: Griffith University

More information

Carmel McDougall, c.mcdougall@griffith.edu.au

FRDC RESEARCH CODES: 2018-118, 2020-021, 2020-043

Exotic oyster invades Queensland waters

A survey of oyster populations in Queensland has identified the presence of the exotic Black Scar Oyster, which has not been found before in Australian waters.

The Black Scar Oyster (Magallana bilineata) has been found at three Far North Queensland locations.

The first discovery in Cairns occurred during a survey of oyster biodiversity being conducted as part of an FRDC-funded project. A commercial fisher in Port Douglas also collected samples from a boat while it was being cleaned and Indigenous rangers discovered a population of the oysters at Cooktown.

Molecular diagnostics of samples from all three locations were performed at Griffith University, in conjunction with Queensland Biosecurity’s Seaports eDNA Surveillance (Q-SEAS) marine pest surveillance program.

The species is abundant in the western Pacific Ocean from the Philippines to Tonga and Fiji, where it was introduced as an aquaculture species.

Biosecurity Queensland is investigating the extent of the incursions and possible control measures. Little is known about this species and its potential impacts, but fisheries managers are keen to minimise its spread in Queensland waters.

Most Black Scar Oysters are difficult to distinguish visually from native counterparts until they reach their distinctive size; they grow to 18 centimetres long, which is much larger than native species. This makes identification in the early stages of the life cycle difficult and significantly limits control options. The Black Scar Oyster has a distinctive muscle scar on the inside of the shell that is much darker than other oysters.

It is found on submerged and floating infrastructure including pylons, pontoons and boats, and can occupy disturbed habitats including shallow subtidal sites.

Boat owners are urged to maintain regular maintenance and cleaning of their vessel to prevent spread, by:

- applying anti-fouling paint;

- cleaning boats in a dry dock or slipway (out of the water); and

- checking and cleaning gear including pots, nets, fishing or diving gear, anchors and ropes, before moving between locations.

A recent increase in exotic marine species detected in Queensland highlights the ongoing threats they may pose and the importance of ongoing marine surveillance activities, including Biosecurity Queensland’s Q-SEAS program.

If you have suspicions about a marine organism contact Biosecurity Queensland on 13 25 23.

The dark muscle scar on the inside of the oyster shell and its large size distinguishes the Black Scar Oyster from native species. Photo: Griffith University

More information

Available on the Queensland Government website.

A report detailing the discovery of Black Scar Oyster in Australia will be published in the Australian journal Molluscan Research.