Models are providing researchers with predictive capability into the effect of climate change on Australia’s fisheries with implications for fisheries management

Illustration: Sonia Kretschmar

By Bianca Nogrady

The fishing industry is no stranger to seasonality. Fish migrate, invertebrates spawn or moult at varying times of year, and larger meteorological forces such as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation change how, where and in what numbers fish and seafood can be harvested. But the changes now being seen in many of Australia’s most significant fisheries are something different. Some stocks are declining despite strict harvest limits, and species are turning up in places that used to be well beyond their comfort zones.

“After more than a decade of having last considered climate change effects on our fisheries we decided it was time to revisit its importance,” says Nick Rayns, executive manager of fisheries management at the Australian Fisheries Management Authority (AFMA).

“And it was only then that we realised climate may be playing a more significant role in our fisheries; it wasn’t just about how much fish the fishing industry was taking out of the water,” he says.

CSIRO, with funding from the FRDC, has delivered a comprehensive, evidence-based projection of the changes likely to occur in Australian fish stocks between now and 2050. The report, Decadal scale projection of changes in Australian fisheries stocks under climate change, was a massive undertaking, says lead author Beth Fulton, group leader at CSIRO Oceans and Atmosphere.

The greater availability of data has allowed this most recent project to make detailed predictions about a wide range of commercial fisheries species, based on extensive modelling. It builds on a legacy of FRDC research into the effects of climate change on Australia’s fishing and aquaculture ongoing since 2009. (For more information on FRDC’s climate adaptation program

of research, led by Colin Creighton, go to the FRDC website).

2050 projection

“It’s the first time, globally, where so many different models have been used to piece together a continental-scale consideration of the effects of climate on the fishing industry,” Beth Fulton says.

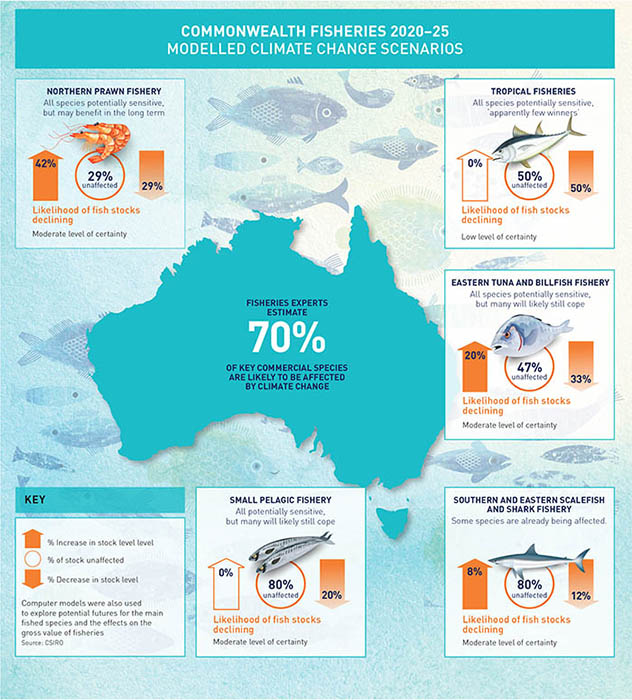

Researchers concluded that 70 per cent of more than 100 key Australian fish species important to commercial, recreational and Indigenous fisheries are sensitive to climate change, along with several protected species.

The abundance, movements, distribution or behaviour of these species could be affected – positively or negatively – by changes in water temperature and the flow-on ecosystem effects of those changes. But predicting these changes is far more complex than a simple ‘physics to fish’ modelling approach, which only takes into account the direct effect of temperature on fish, says CSIRO scientist Alistair Hobday, a co-author of the report.

“Fish don’t eat temperature, they don’t eat chlorophyll, they don’t eat salinity,” Alistair Hobday says. “That tells us that our modelling has to take much greater account of the prey that the fish might eat, because the prey could go up and down, or the prey could move somewhere else.”

The 13 models were all ‘forced’ by temperature, meaning that temperature is the main variable altered. But some models also took into account pH, rainfall and nutrient changes – either directly or via those being forced by changes in productivity predicted by global-scale climate models.

By incorporating several different modelling approaches, researchers were able to see where the different models agreed – giving them greater confidence in the predictions – and where they did not.

In most fisheries, the agreement of models provided a moderate level of certainty in the predicted outcomes. Australia’s tropical fisheries were the exception, with only a low level of certainty (see infographic below).

Infographic: Fiona James

Exposed

Even with these uncertainties, Beth Fulton says she was surprised by the sheer magnitude of the exposure of Australian fisheries to the effects of climate change.

“There’s already more than a hundred species that have shifted distributions and moved further southward,” she says. “There’s been an increasing number of extreme events, particularly affecting the waters around Australia and the marine habitats that our fish species rely on.”But not all species are negatively affected. For example, in the Northern Prawn Fishery, the report found that all species were potentially sensitive to changing climatic effects, but some could benefit in the short term. Similarly, the Eastern Tuna and Billfish Fishery modelling showed about one-fifth of species was likely to benefit from increasing temperatures, and one-third would suffer from them.

Alistair Hobday says the overall trend points to short-term winners but long-term losers.

“Particularly in southern Australia, warming waters might enhance the growth rate of fish, so they’ll grow more quickly, they might have more offspring, but in the long term that temperature increase will have a negative effect,” he says. This is because species have a ‘thermal preference’ – a temperature distribution that best suits them – which is hump-shaped.

“For fish living at temperatures on the uphill side of the hump, as it gets warmer their performance will increase,” he says. “But once you get over the hump and down the other side, as temperatures increase still further, their performance declines.”

For more stationary coastal species, such as scallop, rock lobster and abalone, that temperature increase is more problematic. These species could find it more difficult to relocate the required distances to cooler water.

Pelagic fish species have it a little easier, because they can move southwards or further out to sea to escape the increasing temperatures.

But this raises a major issue for fisheries management: what happens when a species moves beyond the legal boundaries of a fishery?

Fishing boundaries

Beth Fulton

Beth FultonGroup leader at CSIRO Oceans and Atmosphere.

AFMA recently convened a cross-jurisdictional steering committee, made up of representatives from environmental organisations, the commercial and recreational fishing industries, managers and the research community, to address this question. The committee’s aim, over the next year or so, is to explore how adaptable Australian fisheries are, and what can be done to improve their resilience against a changing ocean climate. Nick Rayns says the committee will explore three key issues.

The first issue is fishing boundaries – do they need to be moved to enable industry to remain sustainable and profitable?

The second issue is fishing methods – is more freedom needed in choosing a method to give fishers greater flexibility as fish stocks change in abundance or location?The third issue is fishing rights. The quota fishery system in place allows fishers to take a certain amount of a certain fish stock – but what happens to that quota if that fish stock changes its abundance or range as a result of climate change?

“Similarly, if new fish stocks arise because they’ve become more abundant in a future climate, who gets access to those?” Nick Rayns asks. “How do we actually give future access to what might be a new resource that can be harvested?”

Management rethink

Clayton Nelson, project manager at Austral Fisheries, believes the fishing rights system is likely to need a major rethink to respond to the challenge of climate change. The focus has to be on flexibility in fishing arrangements.

“It’s not just about climate change, it’s about climate change affecting marine parks and marine park boundaries, and migratory fishes – it’s a very complex discussion,” he says.

While effects are already being seen in northern and western abalone stocks, and anecdotal evidence suggests early effects in rock lobsters, there is particular interest in how the Southern Bluefin Tuna Fishery will be affected and how it will adapt.

“They’re a migratory species, but they can move according to water temperatures,” Clayton Nelson says. “How it moves, and if it moves beyond Australian waters, what happens then?”

AFMA convened a workshop in November 2018 bringing together stakeholders to better understand the risks and how those risks may be assessed. Attendees included participants from the US, Canada and New Zealand who face similar climate challenges in their own fisheries.

The development of a formal risk-assessment framework is expected to identify key issues that will need to be addressed in the management of Commonwealth, and possibly other, Australian fisheries.

It is one thing for the fishing industry to adapt, but consumers are just as much of a challenge when it comes to changes in seafood availability.

“I think the industry will do a pretty good job of adaptation, but the consumer has to be brought along with it, which is going to be one of the tougher bits,” Nick Rayns says. “We’re big fans of Snapper, Atlantic Salmon and Barramundi, but if you put seafood someone hasn’t seen before in front of them they tend to be a little cautious.”

Despite the many unknowns, Beth Fulton is optimistic that Australia can still achieve a sustainable fishing industry, even with large-scale ecosystem change.

She says the commercial sector is being proactive in its response to potential climate effects. “They want to do it in an inclusive way that does consult with industry and the public to make sure that everybody understands why change is needed,” she says.

FRDC Research Code: 2016-139

More information

Nick Rayns, AFMA

nick.rayns@afma.gov.au

Beth Fulton, CSIRO

beth.fulton@csiro.au