Fishers are urged to be aware of – and contribute to – national and international biodiversity and conservation policies which will increasingly influence the future of Australian fisheries management.

By Catherine Norwood

It’s a long way from the daily challenges on the deck of an Australian fishing vessel to the rarefied environs of global negotiations on biodiversity conservation, convened under United Nations environment agreements.

But increasingly, these negotiations are impacting the way countries monitor and manage their fisheries, says Dr Kim Friedman.

Kim - an Australian marine scientist involved in many such negotiations over the last decade as a senior fisheries resource officer with the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations says international priorities for nature are primarily the responsibility of government environmental agencies.

“Government ministries responsible for nature include expertise focused on protecting wildlife on land; there is a growing need to strengthen the involvement of sectors related to food production, particularly fisheries, in global negotiations.”

Treaties, such as the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), signed by Australia in 1993, are increasingly gaining influence on fisheries management and trade. This is understandable, as the fisheries sector is reliant on fish stocks in the wild and has daily interactions with biodiversity.

The CBD’s Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework is among the most recent international agreements to affect Australian fisheries management. Adopted in 2022, the framework sets new goals and targets for the CBD.

The Australian Government has already moved to align itself with the framework which has 23 global targets for 2030, in three groups:

-

Reducing threats to biodiversity

-

Meeting people’s needs through sustainable use and benefit-sharing, and

-

Tools and solutions for implementation and mainstreaming.

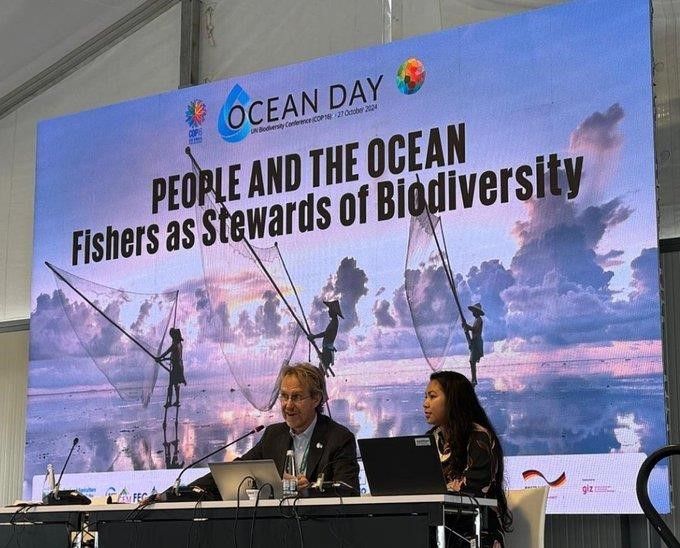

“Fishers won’t necessarily see themselves in the negotiated language of the framework, as they have not been involved in its development from the start,” says Kim. “But overlooking the potential of fishers as environmental stewards, and fishers failing to engage with the framework, could ultimately undermine the long-term conservation aims for marine systems.”

Kim says while fishers may be focused on running their businesses, it is important to keep an eye on the bigger picture. “The fishing sector needs to make sure they're part of the conversation, whether it is intergovernmental biodiversity targets or trade controls.”

“There can be opportunities to showcase the work fisheries have done to conserve biodiversity, and to look for further support. And also, to provide a reality check on the potential impacts.”

He points to the recent addition of many sharks and rays to Appendix II of another treaty, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). Under CITES, international trade of these species now requires government certification. Kim says while the new listings were designed to protect endangered species, they have also captured several widely fished and sustainable stocks of “look alike” shark species.

One of the unintended consequences has been the undermining of livelihoods of fishers, and loss of valuable government time in administration of trade for species that may not be at risk. Creating non-tariff barriers to legal and sustainable trade removes much needed capacity from the delivery of conservation of vulnerable fish stocks, he notes.

FRDC Managing Director Dr Patrick Hone says the Australian Government’s “nature positive” strategy aligns with the Kunming-Montreal framework, including its protection and repair approach for species and ecosystems, and consideration of climate change.

“From a fisheries perspective, the next 10 to 15 years will bring additional requirements for reporting and monitoring from the federal government as part of its commitment to these international treaties.

“Every fishery will need to provide data and assessments for interactions of bycatch with discards and with threatened species,” says Patrick.

“As the government implements agreements such as the Kunming–Montreal framework, we need to better understand climate interactions in the fisheries sector, and how we can put policies in place to manage the changes and uncertainty around fish stocks,” says Patrick.

FRDC's SeaChange Project, led by University of Tasmania Professor Gretta Pecl, is actively developing solutions to help Australia's fishing and aquaculture sectors adapt to and mitigate the impacts of climate change. A core component of SeaChange involves fostering a collaborative knowledge exchange between researchers and industry stakeholders across the nation.

Aligned with FRDC's 'doing more with less' digital strategy, ICT Digitalisation and Insights Manager Kyaw Kyaw Soe Hiang emphasises the need to shift away from reactive data collection – using data once and never again.

“We should be investing in robust data infrastructure, standards, and processes to enable data collection once and utilise it for multiple purposes.”

This strategic approach underscores the value of platforms FRDC is involved in, such as the Australian AgriFood Data Exchange and Research Link Australia, which facilitate efficient data sharing and utilisation.

More information: Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework 2030 Targets