The world’s first global review of microplastics and seafood confirms negative impacts on marine species while identifying the sources of contaminant and suggesting ways to minimise its impact.

Microplastics are now so ubiquitous in the environment they are an almost unavoidable part of the food chain. Trillions of plastic particles are floating in our oceans.

Now a team of researchers from the University of Adelaide has brought together global research showing the potentially harmful effect it has on seafood species. The research also indicates where the microplastics originate. This bridges a knowledge gap that will help to identify threats and opportunities to sustain the fishing and aquaculture sectors.

In a comprehensive review of more than 600 international scientific papers, the FRDC-supported research (2021-117) reveals that 93 per cent of all marine species are negatively affected by microplastics (pieces of plastic smaller than 5mm).

A further 188 studies revealed that worldwide, fishing and aquaculture are responsible for 23 per cent of plastic pollution in the marine and coastal environment.

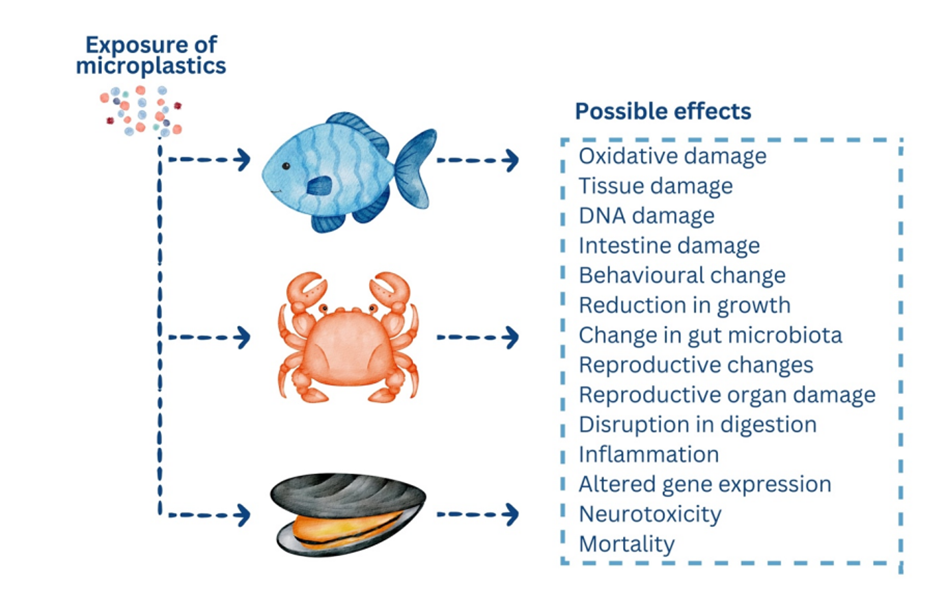

Studies of research in laboratory settings indicated that consuming microplastics caused changes in species’ behaviour, hormone levels, growth, reproduction, and could even result in death.

Negative effects were seen in 94.2 per cent of fish, 90 per cent of crustaceans and 93.5 per cent of molluscs.

“There were growth rate issues and impacts on population health where the viability of offspring to reproduce was compromised,” says Adelaide University marine ecologist Dr Nina Wootton, who trawled through the literature.

Data for prevention

Nina says while the species in the studies were fed significantly higher levels of microplastics than exist in marine environments, it provided baseline data to establish the potential impacts.

This knowledge would help prevent such outcomes in the real world by encouraging practices and technical innovation to reduce plastics in the environment and maintain a healthy ecosystem.

Potential threats of plastic contamination to the seafood sector, including ecological disruption, food safety concerns, market reputation and regulatory and legal pressure, would also be mitigated through these efforts, she says.

“As a starting point, we need to know if it's an issue or not and we've got to that point now,” she says. “And knowledge is so important because you need knowledge to care, and you need to care to take action and think of solutions.”

Leading by example

FRDC Research Portfolio Manager Adrianne Laird says the issue of microplastics has been on the radar of commercial fishers for some time. And Australia will continue to play a “leading role” in a global effort to reduce the impact of plastics on seafood.

“Australian fishing and aquaculture sectors are working to address the issue by investigating their own plastic use and options to reduce it. We have several projects underway, including with wild-caught prawns and rock lobster, looking across supply chains and onboard vessels,” says Adrianne.

Nina says identifying that fishing and aquaculture operations globally are the source of almost a quarter of plastics in the coastal and marine environment could help to propel innovation in the sector and inform policy.

Previous FRDC-funded research (2017-199) from the University of Adelaide team measuring levels of microplastics in seafood itself shows that Australian seafood contains lower levels than the international average.

In oysters, while 49 per cent contained microplastics, it was at a rate of 0.1 pieces per gram – about 15 times lower than the global average. Fish were 3.5 to 4 times lower than the global average with 35 per cent containing microplastic, at a rate of just under one piece per fish.

“We are quite clean compared to international waters,” Nina says. “And even though the levels of plastic we are finding are very low, we are seeing potential to help reduce that even further within fisheries and aquaculture.”

Related FRDC Projects

FRDC Project 2021-117: A global review on implications of plastic in seafood

FRDC Project 2017-199: A preliminary assessment of the prevalence of marine microplastics in Australian fish, crustaceans and molluscs