The principles of ownership and the right to manage and regulate marine resources featured on the agenda of the inaugural Australian Sea Country Conference in 2024.

By Catherine Norwood

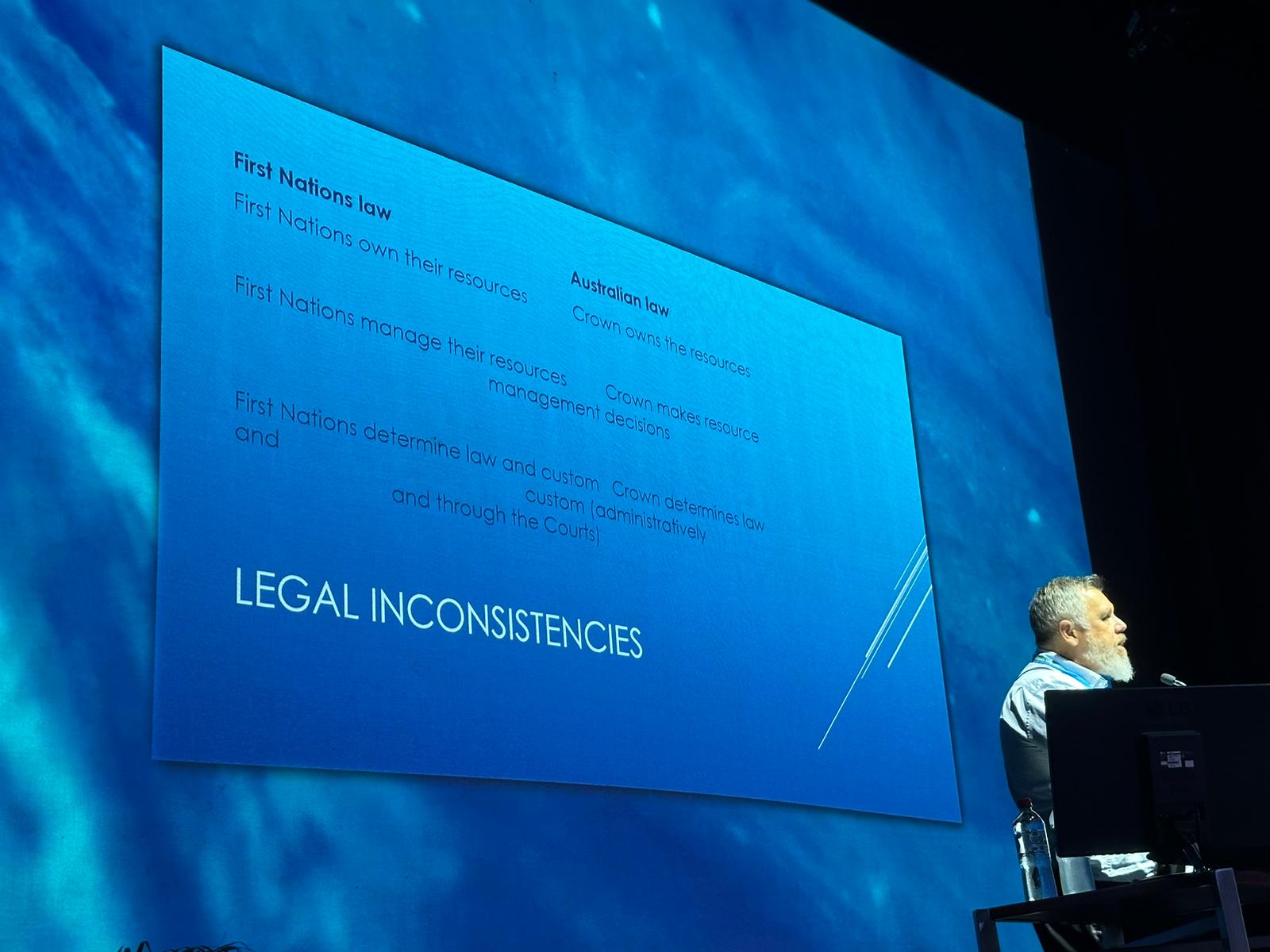

Keynote speaker at Australia’s first Sea Country Conference Tony McAvoy highlighted some fundamental differences between customary and Australian law that he believes affects the way marine resources are managed.

A barrister and senior co-counsel for the Yoorrook Justice Commission truth-telling process in Victoria, Tony gave his views on some of the legal, policy and operational inconsistencies between the customary law of First Nations people and Australian law.

He also outlined processes that he felt would help bridge differences and encourage continued advocacy to recognise Indigenous rights.

Interpreting customary law

Tony says under First Nations law; the First Nations themselves determine how their law and custom applies. Under Australian law, the Crown, through administrative decisions or through the courts, determines how Indigenous law is interpreted and applied.

“For example, with the Native Title Act, most native title determinations say that Indigenous people can exercise the right to hunt and fish subject to the traditional rules and customs.

“If anybody challenges that, then the court decides whether taking fish with a gillnet is taking fish according to Aboriginal law and customs. Under Aboriginal law, nobody else has the right to decide about whether that's according to our law and custom.”

Resource management

He says that while Australia’s First Nations people maintain their right to manage and regulate natural resources, including marine resources, under Australian law these rights are vested in the Crown.

However, he highlights a 1999 Australian High Court decision in the case of Yanner versus Eaton that held that the vesting of natural resources in the government represented an arrangement for management and regulation but did not represent “ownership”. Tony says the High Court determined that this vesting did not extinguish Indigenous ownership of natural resources.

While the High Court case applied to terrestrial native species in Queensland, he says it has broader implications for both land and marine natural resources management across all Australian jurisdictions.

“There is a question that needs to be resolved around how the continuing rights of First Nations people can be accommodated in a system that regulates use by everybody. This hasn’t really been properly tackled in any policy or legal sense in Australia.”

Informed consent

He points to international law and the development of free prior informed consent (FPIC) policies in Australia’s management of natural resources as key to making this happen.

FPIC is supported by the United Nations Declaration on Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP), to which Australia is a signatory. FPIC is required for any undertaking that affects Indigenous peoples’ rights to land, territory and resources, including mining and the use or exploitation of resources.

In Australia, in a fisheries context, Tony believes this mechanism should be established in each fisheries’ jurisdiction to ensure relevant First Nations people have the opportunity to give their free prior informed consent to fisheries management principles and plans.

“That doesn’t happen in Australia,” notes Tony. “To do that, there needs to be some substantial changes to fisheries management regimes so First Nations People are treated at the very least as co-owners of the resource and are enabled to make proper, informed decisions about how resources are sustainably managed.”

He says the role of continued advocacy by First Nations communities is essential in directing change. This includes creating a First Nations FIPC policy outlining how the process should work.

“They can then ask governments and industry to comply as ‘good partners’,” he explains.

His final recommendations to the Sea Country Conference include continuing to advocate for recognition of First Nations ownership of the resources, to seek full respect for free prior informed consent and for coordinated participation in the fisheries sector at all levels.

Related FRDC Project

2024-013: Australian Sea Country Conference